- India

- International

Global Hunger Index: A survey that trivialised hunger

Bibek Debroy writes: It made serious errors in classification, methodology

Why does one construct such indices? Presumably to influence policy. So, there is a normative angle to such an exercise. It isn’t merely academic and intellectual.

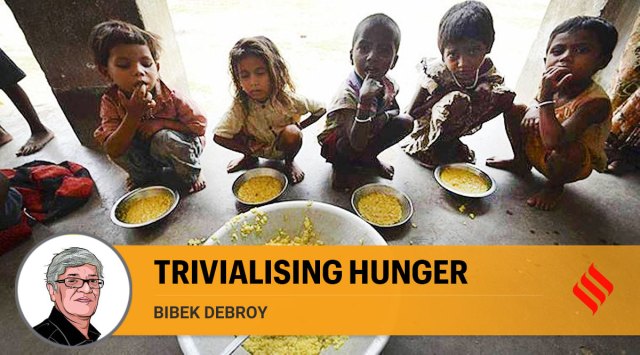

Why does one construct such indices? Presumably to influence policy. So, there is a normative angle to such an exercise. It isn’t merely academic and intellectual.The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 has several terms clubbed together, as befits a goal – hunger, food security, nutrition and sustainable agriculture. That doesn’t mean these terms are synonymous. Only the foolhardy will attempt to measure the sustainability of agriculture through data on nutrition. Therefore, in refining goals, SDG-2 has separate targets on under-nourishment, food insecurity, stunting (height for age) and malnutrition (weight for height).

It is difficult to distinguish under-nourishment from malnutrition and the FAO tends to equate food insecurity with malnutrition and equate that with hunger. With India’s subsidised food security schemes, hunger isn’t likely to be a problem. Indeed, the National Sample Survey’s consumption surveys showed almost every household, rural and urban, reported getting two square meals a day. The discourse should shift from hunger to malnutrition. That’s the reason India’s national indicator framework for SDGs (developed by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation) has indicators like under-weight, stunted and wasted under-five children, anaemic pregnant women and children, women with low BMI and marginalised populations without access to subsidised food-grains. To state the obvious again, since it isn’t often appreciated, what’s true of children, or women for that matter, need not be true of the general population. When dealing with numbers, it is best to remember this.

Along comes the GHI (Global Hunger Index), with a self-proclaimed peer-reviewed methodology. There are four indicators – under-nourishment, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality. Since these are the indicators, how accurate is it to call this a hunger index? One-sixth of the weightage is attached to child stunting, 1/6th to child wasting, 1/3rd to child mortality and 1/3rd to under-nourishment. The nomenclature of “hunger” is driven by under-nourishment, which is for the entire population, not merely children.

Why does one construct such indices? Presumably to influence policy. So, there is a normative angle to such an exercise. It isn’t merely academic and intellectual. Under “policy”, we are given the somewhat vacuous general statement: “The 2022 GHI reflects both the scandal of alarming hunger in too many countries across the world as well as the changing trajectory in countries where decades of progress in tackling hunger is being eroded.” There is no particular mention of children, or women, in this, suggesting the policy intention is to emphasise hunger, not the other indicators, even if they figure in the index. All policy statements have value judgements. Is an increase in child stunting and child wasting necessarily bad? Most people will probably automatically answer in the affirmative. However, child and infant mortality has been declining simultaneously. Surely, that’s a good thing. These are children who would otherwise have died. Now born, they are now likely to be under-weight, stunted and wasted, compared to the average and that will pull down the numbers.

Had the methodology been truly peer-reviewed, and not cheer-reviewed, the likelihood is high a critique would have suggested separation of indicators for the general population from those for children. That enables a teasing out of policy, distinct for the two segments. For indicators connected with children, we have numbers from NFHS-5 (National Family Health Survey), conducted between 2019 and 2021. The UNDP’s recent report on multi-dimensional poverty has used this to document declines in poverty. Thus, one understands where data for three of the four indicators comes from. Data come through surveys, not from complete enumeration, as happens with a census.

Nonetheless, the sample size of the NFHS is large enough. Where did the FAO get data on under-nourishment or hunger, the fourth indicator? This isn’t data that any standard survey gets numbers on. FAO decided to do its own survey, as it has in the past, through its Food Insecurity Experience Scale Survey Module, which has eight questions. As most people know by now, this poll was administered to a sample size of 3,000. In an era, where a chat with a single taxi-driver offers policy insights, 3,000 may seem large. But in a country like India, most people would laugh at this sample size.

Peer-reviewed or not, the questions seem odd to anyone who has drafted questionnaires. For example, question 8 states, as a question being asked, “You went without eating for a whole day because of a lack of money or other resources?” This is fine. But question 1 states, “You were worried you would not have enough food to eat because of a lack of money or other resources?” There should be grave reservations about questions that concern the state of the mind. It gets worse. Surely, the questions weren’t asked in English. Yes, they were asked in Hindi. Question 6 states, “Your household ran out of food because of a lack of money or other resources?” The Hindi translation, as was asked, is “apke ghar mein bhojana ki kami ho gayi kyonki ghar mei paise ya anya samashadano ki kami thi”. “Running out” means there is no food. “Kami” means less food. Answering yes to the Hindi question isn’t the same as answering yes to the English question.

This is more than mere semantics. It is a serious error in translation. Such errors can be due to incompetence, or they can be deliberate. In an exercise that has been peer-reviewed and must have gone through successive iterations, incompetence and inadvertence is unlikely to be the answer. In any event, by propagating something like GHI, the FAO has done a great disservice to itself, trivialising a serious issue, where cross-country surveys on hunger in other countries must also have been subject to serious anomalies.

The writer is chairman, PM’s Economic Advisory Council. Views are personal

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

May 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05