I wanted to call the new album One Nation Under Sedation,” says George Clinton. “But instead I called it Medicaid Fraud Dogg.”

The first Parliament album since 1980’s Trombipulation includes contributions from long-time Funkateers Fred Wesley, Pee Wee Ellis, Greg Thomas and Benny Cowan, and is typical Clinton weltanschauung.

“It’s like everyone’s a legalised junkie these days,” he explains of the motivation behind the title and subject – the US health care system and the pharmaceutical business. “They prescribe us pills to get better, then prescribe us more pills to get better from the pills they’ve just given us and they get us hooked. So I’ve got the dope dogs sniffing out the real medication fraud on the record: the pharmaceuticals, the insurance, the government, the lobbies – they’re all in it together. They’re the ones making us sick.”

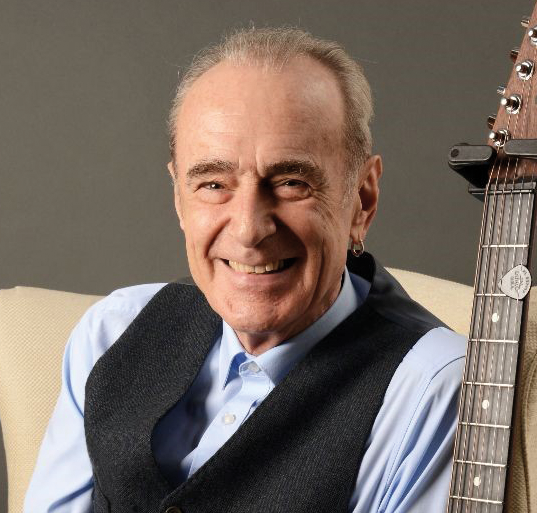

Clinton, now 76, has never sounded healthier. Having given up crack almost a decade ago, he’s lucid, with memory clearly intact. He says he will be giving up touring next year but plans to continue recording “music with a message”. His group’s stage costumes and songs’ fantastical vignettes are, he says, “food for thought, to make the audience question and think.”

His musical career began in 1956 with soul vocal harmony group The Parliaments, who had their first US Top 40 hit with 1967’s (I Wanna) Testify. Since then he’s recorded prolifically as Parliament and Funkadelic – the two collectives sharing personnel, but the first rooted in soul, the second stretching the notions of the funk rock band – then also under his own name and the P-Funk All Stars.

“Funk is the antidote,” he decides ahead of our hour together. “Doesn’t matter how sick anyone gets. It always was, is and will be.”

How did The Parliaments get together?

I was in Plainfield, New Jersey, I had my barber’s shop, the Silk Palace, and Eddie Hazel, Billy Bass Nelson, Tiki Fulwood, Bernie Worrell, they were all teenagers and they came in to get their hair done – everyone wanted a process at that time, the musicians, pimps, preachers – and that was the beginning, that’s where we got the concept together for the band. Eddie was like my kid.

I raised him, got his first guitar and they all went to school together, went to church together, they did everything together.

You tell an excellent story in your (2014) autobiography – Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard On You? – of how you paid for your first studio time with counterfeit money. Is that true?

Yes. These two skinny white kids came running in, they were really nervous, they had this box of fake 20-dollar bills and they wanted $2,000 for them. We scraped together about $1,800 and they gave us them and fled. They just wanted rid of them. We went into the studio, we made our demo, the studio knew we were paying in fake money but we gave them five times more than their usual fee so everyone was real happy with the outcome.

I also did up the Silk Palace, shared some of it out around the community and then when the police came looking for it, dumped a whole load. By then, though, it had served its purpose and I didn’t want to get caught.

Had you always wanted to be a musician?

Yes, from the first time I heard Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers I wanted to sing. That was the wake-up call. Then when I heard Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry’s Maybellene, that was something. I was getting my hands whipped at the time and

I heard the song come on and I just went into this blank stare. And then there was Motown. Once I heard Smokey Robinson I wanted to write, and the groups like The Temptations, they were the basis for The Parliaments’ sound, with their vocal harmonies.

You worked at Motown’s publishing company Jobete for a time. What did you learn there?

Everything about being a professional musician, writer, singer, promoter, producer, arranger. My job was to write songs and get singers to sing them. Or a singer would come in and I’d have to find them a song that suited them. The first one I did was Tamala Lewis’ You Won’t Say Nothing.

Writing and producing Theresa Lindsay’s

I Bet You was a big one for you, wasn’t it?

Definitely. We met Ed Wingate, he ran the Golden World label in Detroit. He wanted me and Sidney Barnes and Mike Terry, my writing partners, to become his main team at the label, and he was hoping we’d eventually rival Motown, be the new Holland-Dozier-Holland. He told us to write Theresa

a song based around this phrase this WJLB radio DJ who called herself Martha Jean The Queen said, which ended, “I bet you.” He put us in one of the motels he owned with a piano and we wrote the song. Theresa had a great voice, then we did the song as Funkadelic, and then The Jackson 5 covered it.

How did you make the musical leap from the 60s Motown-esque Parliaments songs such as Heart Trouble, I Can Feel The Ice Melting, Testify etc to the strange, skewed funk-rock of Funkadelic’s self-titled debut album in 1970?

The Beatles. Sgt Pepper’s came out and it was mind-blowing. The Beatles made it so a band could do any type of music. You know, Who Says A Funk Band Can’t Play Rock? [the title of a 1978 Funkadelic single]. The whole P-Funk concept came from that. Music For My Mother was the first track where I felt

I could do that; it was a conscious decision

to make the move from Temptations soul

to psychedelic funk.

Did it feel liberating?

It was totally liberating with those first Funkadelic albums [1970’s Funkadelic; the same year’s Free Your Mind And Your Ass Will Follow; 1971’s Maggot Brain], which really came out of our jam sessions onstage. We played these long psychedelic grooves, broken into different chants and freestyled over them. We knew how to structure a song. To be so unstructured was liberating for us.

How important was LSD to the

P-Funk vision?

In those early days, it led to creativity. I’d be tripping and come up with “Free your mind and your ass will follow” and we had a friend who would write down what I was saying. But then, after Woodstock, it became business. Before it was, “Want to share some acid?” After, it was $20 for a tab. It became about money so it got cut and suddenly you had to avoid the brown acid…

When I had the barbers, all my customers were junkies: they’d be nodding out in the chair. We had one, he thought he was snorting coke but it was actually skag, and that led to the song Super Stupid. We used to look out

at the corner and watch our favourite nod; everybody on the street was nodding in a different style. They didn’t nod like a wino, they were cool.

By the way, you’re completely clean now, aren’t you?

I’m on no meds, legal or otherwise. I got off crack. The first time you take it, you think

it blows your mind; it does, but you never

get that first-time feeling again. I gave it up when I had to get serious, sort out the finances. I’ve got a pacemaker, but that’s just because of old age.

The first Parliament album, 1970’s Osmium – on Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Invictus label – is one of soul’s most esoteric outings…

At the time I saw Osmium as being quite straight, us trying to continue the Motown sound into the 70s with traditional soulful songs that would get radio play, while with Funkadelic we were stretching the notions of what was expected of soul music, creating this alien world with long jams and stage costumes. As it turned out, Funkadelic was more popular and Osmium mainly sold on the back of people liking Funkadelic, as they knew it was the same band. Then, when we signed to Casablanca with Neil Bogart after that first album, we went back to Parliament with new ideas, a kind of Beatles with strings and horns and James Brown’s funk and jazz.

Osmium features two songs co-written with Ruth Copeland, a folk singer from County Durham who ended up in Detroit with Holland-Dozier-Holland, who were marketing her as the new Diana Ross.

How did that coupling come about?

Ruth was signed to Invictus and married to Jeffrey Bowen, the Motown songwriter, producer and A&R man who had gone with Holland-Dozier-Holland when they left Motown to start Invictus. Jeffrey Bowen suggested we re-start The Parliaments as Parliament and Ruth wrote Little Ole Country Boy and The Silent Boatman for us on the album, then Parliament/Funkadelic backed her on her solo album [1970’s Self Portrait]. She was impressive, a good writer.

What was going through your head when you heard Eddie Hazel play his guitar solo on Maggot Brain for the first time?

Man, it was just extraordinary. You could tell Eddie to do something and he’d understand it straight away. So I said, “Play like your mother just died” and he was quiet for a second, then out it came. He did it in one take. He wallowed in misery and made it beautiful.

He did his best playing in the blues form like Jimi Hendrix, but this was really soulful. My mother used to call him “Old crying Eddie”. She’d hear him play two notes

and she’d be, “There goes that old crying Eddie again.”

Miles Davis was a fan…

He heard something in Wars Of Armageddon; he thought it was free jazz, he was inspired by it on On The Corner, and he even took our drummer Tiki [Fulwood] for his band for

a time.

Did you see yourselves as part of a movement? Albums like Funkadelic’s America Eats Its Young (1972) and Parliament’s Chocolate City (1975) are truly radical, conscious funk/soul.

We were doing our own thing. We knew the civil rights thing was going on, we knew Vietnam was going on, and we reacted in our own way. We were cutting up flags and turning them into uniforms and wearing them onstage; we were part of the hippie movement, tripping on it all and making music that came out of the experience.

Then our fanbase, the college kids from Toronto, Oakland, Berkeley and all over, they’d tell us about their studies, about WEB DuBois, and how we fitted into all these theories, and that started to fuel our activity.

Where did the concept of aliens coming from outer space to save our world with P-Funk come from?

I was looking to create something far-out.

I loved Star Trek and that gave me lots of themes to play with. After Chocolate City, where we took black people into the White House, I then thought, Why not take them into outer space?

Which you did on 1975’s Mothership Connection. What did Casablanca label boss Neil Bogart say when you told him you wanted a space ship on the cover of your record and then a life-size model for your stage show?

Neil never said “no” to us. He was a promotions man, he knew what I was thinking. He knew it was the greatest promotion gimmick so he went with it right away. The one on the album cover is the ship used in [1951 film] The Day The Earth Stood Still and we rented it from the film prop department. Then Neil got us a million-dollar loan, we got a designer [Jules Fisher] and we got our ship. The first time we used it in New Orleans, we had the ship come onstage before we did and we just couldn’t follow it. It stole the show. The next night in Baton Rouge we ended the show with the mothership coming down. It made the perfect finale.

You and Bootsy actually had a UFO encounter. Can you tell me about it?

We were in Toronto, driving home to Detroit. It was morning and we saw this light, like

a laser. It went across the sky, and each time it hit the ground it splattered like electricity. The third time it did this, it hit the car on the side I was in and the light turned to liquid like mercury out of a thermometer. By this time it was dark outside and all the street lights were on and then flickered and went off.

We’d only travelled a few miles down

the road but it had gone from morning to night in what was usually a three-to-four-hour trip. I got home just as my daughter was going to bed. What happened to all that time in between? It took us years to piece it all together.

Sleeve designer Pedro Bell was integral to the P-Funk myth. Who was he?

He was a Funkadelic freak and used to write me letters with all kinds of drawings on; real, proper illustrations, and the postman thought I was a part of some kind of organisation as these letters were so weird and detailed. But

I liked his cartoons so I asked him to do the cover to Cosmic Slop [1973]. I didn’t give him any idea what I wanted, he interpreted the title his way and it became part of Funkadelic.

What was the idea behind spin-off projects Brides Of Funkenstein and Parlet?

Neil wanted a female version of Parliament/Funkadelic, so they were our counterparts, like The Four Tops and The Supremes; they were our take on the female groups at Motown. The Brides, Dawn Silva and Lynn Mabry, had been in a lineup of Sly’s Family Stone and were spun into the story of The Clones Of Dr Funkenstein. Parlet were made up of Mallia Franklin, Jeanette Washington and Debbie Wright and were the female Parliament.

Fred Wesley told me that when he and Maceo Parker joined Funkadelic after playing with James Brown it was “totally freeing, a mind-bomb.” How was it for you?

Fred and Maceo were and are the easiest people in the world to work with. James had them so disciplined and I said to them, “Just do what you do; do you.” They knew what to do, so we did our stuff, they did their stuff, and it worked well.

How did that compare to working with, say, Bootsy Collins, Bernie Worrell and Junie Morrison in the studio?

With Bootsy, who’d also been in James Brown’s band, you didn’t even know what he was doing; you just had to accept it and work around it. It was hard to figure just how he did what he did. Then with Bernie, he made it all come together, he was a musical genius, classically trained. He could see the whole thing, he brought in his jazz and classical ideas. Then when Junie Morrison came in on [1978’s] One Nation Under A Groove, they’d be doing their piano exercises together and putting them on the records. Junie was good at everything, too.

After Parliament/Funkadelic you went solo with 1982’s Computer Games.

It was still the same musicians – Bootsy, Fred Wesley, Garry Shider, Junie, Maceo, the Brides – but I had to use my name because recording under Parliament/Funkadelic was getting me in trouble with the labels. The only way I could make a new record was to be George Clinton. Then when I got into trouble with that I formed the P-Funk Allstars.

Loopzilla was the first single and immortalised Afrika Bambaataa.

Take a look at the back of the sleeve to [Funkadelic’s 1979] Uncle Jam Wants You

and the first name as a part of the fanclub is Afrika Bambaataa: he was telling us about

hip-hop before anyone had put a record out. He explained to us about tapes and rapping over them.

You were an early champion of Prince.

It was obvious P-Funk was running through his veins. He had The Revolution and The Time; he wrote and produced for Sheila E, the Family, Jill Jones, he had Camille, he had this work ethic. It was obvious for everyone to see, he put his heart and soul into everything he did and, once he got with Andre Cymone, they were really dangerous.

You signed to Prince’s Paisley Park for two albums, 1989’s The Cinderella Theory and 1993’s Hey Man… Smell My Finger. How involved was he in the studio?

I called him up, said I need a label and he signed me. He was real quiet, methodical. I’d send him something, he’d play on it and send it back. He was very polite. He came into the studio said “hi” but that was it. We had Chuck D and Flavor Flav on one of the tracks [Tweakin’] but for the most part it was me working with the band I had worked with on my solo stuff at Capitol. For the next album

I said to him, “Don’t be so nice, put some more of your thing on there.” And so he did.

More recently you worked with Kendrick Lamar on his 2015 album, To Pimp A Butterfly. Likeminded souls?

Yes. He’s like the new Funkadelic, he’s got the same imagination and silliness, but he’s also got the poetry, the spirit. He’s talking about the same social and political issues and we clicked immediately. My grandkids turned me onto him. They said, “He talks about the same stuff as you.” He’s like an old soul. He’s had a lot of schooling and he works it into the street he grew up in. He’s the funk now.

Medicaid Fraud Dogg is out now on

C Kunspyruhzy Records Inc.

I wanted to call the new album One Nation Under Sedation,” says George Clinton. “But instead I called it Medicaid Fraud Dogg.”

The first Parliament album since 1980’s Trombipulation includes contributions from long-time Funkateers Fred Wesley, Pee Wee Ellis, Greg Thomas and Benny Cowan, and is typical Clinton weltanschauung.

“It’s like everyone’s a legalised junkie these days,” he explains of the motivation behind the title and subject – the US health care system and the pharmaceutical business. “They prescribe us pills to get better, then prescribe us more pills to get better from the pills they’ve just given us and they get us hooked. So I’ve got the dope dogs sniffing out the real medication fraud on the record: the pharmaceuticals, the insurance, the government, the lobbies – they’re all in it together. They’re the ones making us sick.”

Clinton, now 76, has never sounded healthier. Having given up crack almost

a decade ago, he’s lucid, with memory clearly intact. He says he will be giving up touring next year but plans to continue recording “music with a message”. His group’s stage costumes and songs’ fantastical vignettes are, he says, “food for thought, to make the audience question and think.”

His musical career began in 1956 with soul vocal harmony group The Parliaments, who had their first US Top 40 hit with 1967’s (I Wanna) Testify. Since then he’s recorded prolifically as Parliament and Funkadelic – the two collectives sharing personnel, but the first rooted in soul, the second stretching the notions of the funk rock band – then also under his own name and the P-Funk All Stars.

“Funk is the antidote,” he decides ahead of our hour together. “Doesn’t matter how sick anyone gets. It always was, is and will be.”

How did The Parliaments get together?

I was in Plainfield, New Jersey, I had my barber’s shop, the Silk Palace, and Eddie Hazel, Billy Bass Nelson, Tiki Fulwood, Bernie Worrell, they were all teenagers and they came in to get their hair done – everyone wanted a process at that time, the musicians, pimps, preachers – and that was the beginning, that’s where we got the concept together for the band. Eddie was like my kid.

I raised him, got his first guitar and they all went to school together, went to church together, they did everything together.

You tell an excellent story in your (2014) autobiography – Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard On You? – of how you paid for your first studio time with counterfeit money. Is that true?

Yes. These two skinny white kids came running in, they were really nervous, they had this box of fake 20-dollar bills and they wanted $2,000 for them. We scraped together about $1,800 and they gave us them and fled. They just wanted rid of them. We went into the studio, we made our demo, the studio knew we were paying in fake money but we gave them five times more than their usual fee so everyone was real happy with the outcome.

I also did up the Silk Palace, shared some of it out around the community and then when the police came looking for it, dumped a whole load. By then, though, it had served its purpose and I didn’t want to get caught.

Had you always wanted to be a musician?

Yes, from the first time I heard Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers I wanted to sing. That was the wake-up call. Then when I heard Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry’s Maybellene, that was something. I was getting my hands whipped at the time and

I heard the song come on and I just went into this blank stare. And then there was Motown. Once I heard Smokey Robinson I wanted to write, and the groups like The Temptations, they were the basis for The Parliaments’ sound, with their vocal harmonies.

You worked at Motown’s publishing company Jobete for a time. What did you learn there?

Everything about being a professional musician, writer, singer, promoter, producer, arranger. My job was to write songs and get singers to sing them. Or a singer would come in and I’d have to find them a song that suited them. The first one I did was Tamala Lewis’ You Won’t Say Nothing.

Writing and producing Theresa Lindsay’s

I Bet You was a big one for you, wasn’t it?

Definitely. We met Ed Wingate, he ran the Golden World label in Detroit. He wanted me and Sidney Barnes and Mike Terry, my writing partners, to become his main team at the label, and he was hoping we’d eventually rival Motown, be the new Holland-Dozier-Holland. He told us to write Theresa

a song based around this phrase this WJLB radio DJ who called herself Martha Jean The Queen said, which ended, “I bet you.” He put us in one of the motels he owned with a piano and we wrote the song. Theresa had a great voice, then we did the song as Funkadelic, and then The Jackson 5 covered it.

How did you make the musical leap from the 60s Motown-esque Parliaments songs such as Heart Trouble, I Can Feel The Ice Melting, Testify etc to the strange, skewed funk-rock of Funkadelic’s self-titled debut album in 1970?

The Beatles. Sgt Pepper’s came out and it was mind-blowing. The Beatles made it so a band could do any type of music. You know, Who Says A Funk Band Can’t Play Rock? [the title of a 1978 Funkadelic single]. The whole P-Funk concept came from that. Music For My Mother was the first track where I felt

I could do that; it was a conscious decision

to make the move from Temptations soul

to psychedelic funk.

Did it feel liberating?

It was totally liberating with those first Funkadelic albums [1970’s Funkadelic; the same year’s Free Your Mind And Your Ass Will Follow; 1971’s Maggot Brain], which really came out of our jam sessions onstage. We played these long psychedelic grooves, broken into different chants and freestyled over them. We knew how to structure a song. To be so unstructured was liberating for us.

How important was LSD to the

P-Funk vision?

In those early days, it led to creativity. I’d be tripping and come up with “Free your mind and your ass will follow” and we had a friend who would write down what I was saying. But then, after Woodstock, it became business. Before it was, “Want to share some acid?” After, it was $20 for a tab. It became about money so it got cut and suddenly you had to avoid the brown acid…

When I had the barbers, all my customers were junkies: they’d be nodding out in the chair. We had one, he thought he was snorting coke but it was actually skag, and that led to the song Super Stupid. We used to look out

at the corner and watch our favourite nod; everybody on the street was nodding in a different style. They didn’t nod like a wino, they were cool.

By the way, you’re completely clean now, aren’t you?

I’m on no meds, legal or otherwise. I got off crack. The first time you take it, you think

it blows your mind; it does, but you never

get that first-time feeling again. I gave it up when I had to get serious, sort out the finances. I’ve got a pacemaker, but that’s just because of old age.

The first Parliament album, 1970’s Osmium – on Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Invictus label – is one of soul’s most esoteric outings…

At the time I saw Osmium as being quite straight, us trying to continue the Motown sound into the 70s with traditional soulful songs that would get radio play, while with Funkadelic we were stretching the notions of what was expected of soul music, creating this alien world with long jams and stage costumes. As it turned out, Funkadelic was more popular and Osmium mainly sold on the back of people liking Funkadelic, as they knew it was the same band. Then, when we signed to Casablanca with Neil Bogart after that first album, we went back to Parliament with new ideas, a kind of Beatles with strings and horns and James Brown’s funk and jazz.

Osmium features two songs co-written with Ruth Copeland, a folk singer from County Durham who ended up in Detroit with Holland-Dozier-Holland, who were marketing her as the new Diana Ross.

How did that coupling come about?

Ruth was signed to Invictus and married to Jeffrey Bowen, the Motown songwriter, producer and A&R man who had gone with Holland-Dozier-Holland when they left Motown to start Invictus. Jeffrey Bowen suggested we re-start The Parliaments as Parliament and Ruth wrote Little Ole Country Boy and The Silent Boatman for us on the album, then Parliament/Funkadelic backed her on her solo album [1970’s Self Portrait]. She was impressive, a good writer.

What was going through your head when you heard Eddie Hazel play his guitar solo on Maggot Brain for the first time?

Man, it was just extraordinary. You could tell Eddie to do something and he’d understand it straight away. So I said, “Play like your mother just died” and he was quiet for a second, then out it came. He did it in one take. He wallowed in misery and made it beautiful.

He did his best playing in the blues form like Jimi Hendrix, but this was really soulful. My mother used to call him “Old crying Eddie”. She’d hear him play two notes

and she’d be, “There goes that old crying Eddie again.”

Miles Davis was a fan…

He heard something in Wars Of Armageddon; he thought it was free jazz, he was inspired by it on On The Corner, and he even took our drummer Tiki [Fulwood] for his band for

a time.

Did you see yourselves as part of a movement? Albums like Funkadelic’s America Eats Its Young (1972) and Parliament’s Chocolate City (1975) are truly radical, conscious funk/soul.

We were doing our own thing. We knew the civil rights thing was going on, we knew Vietnam was going on, and we reacted in our own way. We were cutting up flags and turning them into uniforms and wearing them onstage; we were part of the hippie movement, tripping on it all and making music that came out of the experience.

Then our fanbase, the college kids from Toronto, Oakland, Berkeley and all over, they’d tell us about their studies, about WEB DuBois, and how we fitted into all these theories, and that started to fuel our activity.

Where did the concept of aliens coming from outer space to save our world with P-Funk come from?

I was looking to create something far-out.

I loved Star Trek and that gave me lots of themes to play with. After Chocolate City, where we took black people into the White House, I then thought, Why not take them into outer space?

Which you did on 1975’s Mothership Connection. What did Casablanca label boss Neil Bogart say when you told him you wanted a space ship on the cover of your record and then a life-size model for your stage show?

Neil never said “no” to us. He was a promotions man, he knew what I was thinking. He knew it was the greatest promotion gimmick so he went with it right away. The one on the album cover is the ship used in [1951 film] The Day The Earth Stood Still and we rented it from the film prop department. Then Neil got us a million-dollar loan, we got a designer [Jules Fisher] and we got our ship. The first time we used it in New Orleans, we had the ship come onstage before we did and we just couldn’t follow it. It stole the show. The next night in Baton Rouge we ended the show with the mothership coming down. It made the perfect finale.

You and Bootsy actually had a UFO encounter. Can you tell me about it?

We were in Toronto, driving home to Detroit. It was morning and we saw this light, like

a laser. It went across the sky, and each time it hit the ground it splattered like electricity. The third time it did this, it hit the car on the side I was in and the light turned to liquid like mercury out of a thermometer. By this time it was dark outside and all the street lights were on and then flickered and went off.

We’d only travelled a few miles down

the road but it had gone from morning to night in what was usually a three-to-four-hour trip. I got home just as my daughter was going to bed. What happened to all that time in between? It took us years to piece it all together.

Sleeve designer Pedro Bell was integral to the P-Funk myth. Who was he?

He was a Funkadelic freak and used to write me letters with all kinds of drawings on; real, proper illustrations, and the postman thought I was a part of some kind of organisation as these letters were so weird and detailed. But

I liked his cartoons so I asked him to do the cover to Cosmic Slop [1973]. I didn’t give him any idea what I wanted, he interpreted the title his way and it became part of Funkadelic.

What was the idea behind spin-off projects Brides Of Funkenstein and Parlet?

Neil wanted a female version of Parliament/Funkadelic, so they were our counterparts, like The Four Tops and The Supremes; they were our take on the female groups at Motown. The Brides, Dawn Silva and Lynn Mabry, had been in a lineup of Sly’s Family Stone and were spun into the story of The Clones Of Dr Funkenstein. Parlet were made up of Mallia Franklin, Jeanette Washington and Debbie Wright and were the female Parliament.

Fred Wesley told me that when he and Maceo Parker joined Funkadelic after playing with James Brown it was “totally freeing, a mind-bomb.” How was it for you?

Fred and Maceo were and are the easiest people in the world to work with. James had them so disciplined and I said to them, “Just do what you do; do you.” They knew what to do, so we did our stuff, they did their stuff, and it worked well.

How did that compare to working with, say, Bootsy Collins, Bernie Worrell and Junie Morrison in the studio?

With Bootsy, who’d also been in James Brown’s band, you didn’t even know what he was doing; you just had to accept it and work around it. It was hard to figure just how he did what he did. Then with Bernie, he made it all come together, he was a musical genius, classically trained. He could see the whole thing, he brought in his jazz and classical ideas. Then when Junie Morrison came in on [1978’s] One Nation Under A Groove, they’d be doing their piano exercises together and putting them on the records. Junie was good at everything, too.

After Parliament/Funkadelic you went solo with 1982’s Computer Games.

It was still the same musicians – Bootsy, Fred Wesley, Garry Shider, Junie, Maceo, the Brides – but I had to use my name because recording under Parliament/Funkadelic was getting me in trouble with the labels. The only way I could make a new record was to be George Clinton. Then when I got into trouble with that I formed the P-Funk Allstars.

Loopzilla was the first single and immortalised Afrika Bambaataa.

Take a look at the back of the sleeve to [Funkadelic’s 1979] Uncle Jam Wants You

and the first name as a part of the fanclub is Afrika Bambaataa: he was telling us about

hip-hop before anyone had put a record out. He explained to us about tapes and rapping over them.

You were an early champion of Prince.

It was obvious P-Funk was running through his veins. He had The Revolution and The Time; he wrote and produced for Sheila E, the Family, Jill Jones, he had Camille, he had this work ethic. It was obvious for everyone to see, he put his heart and soul into everything he did and, once he got with Andre Cymone, they were really dangerous.

You signed to Prince’s Paisley Park for two albums, 1989’s The Cinderella Theory and 1993’s Hey Man… Smell My Finger. How involved was he in the studio?

I called him up, said I need a label and he signed me. He was real quiet, methodical. I’d send him something, he’d play on it and send it back. He was very polite. He came into the studio said “hi” but that was it. We had Chuck D and Flavor Flav on one of the tracks [Tweakin’] but for the most part it was me working with the band I had worked with on my solo stuff at Capitol. For the next album

I said to him, “Don’t be so nice, put some more of your thing on there.” And so he did.

More recently you worked with Kendrick Lamar on his 2015 album, To Pimp A Butterfly. Likeminded souls?

Yes. He’s like the new Funkadelic, he’s got the same imagination and silliness, but he’s also got the poetry, the spirit. He’s talking about the same social and political issues and we clicked immediately. My grandkids turned me onto him. They said, “He talks about the same stuff as you.” He’s like an old soul. He’s had a lot of schooling and he works it into the street he grew up in. He’s the funk now.

Medicaid Fraud Dogg is out now on

C Kunspyruhzy Records Inc.