Darren Aronofsky | 1hr 42min

As monstrous as drug addiction is in Requiem for a Dream, Darren Aronofsky does not simply confine the film’s horror to the violent psychological, physical, and emotion effects substance abuse wreaks on human minds and bodies. For each of our four interconnected main characters, there is a sharp, sudden decline they all experience in the final act, turning them from barely functioning members of society to broken victims dismissed as junkies, whores, delinquents, and lunatics. The drug trade of this cinematic fever dream is simply one arm of a rigid class system used to placate those who grow too restless in their station, ensuring that any ‘cheating’ attempts at upwards social mobility only push them further in the opposite direction. In this downward spiral, Aronofsky’s kinetic style alternates between short, jerky rhythms and languid, groggy movements, absorbing us into a nightmare of purely disorientating maximalism that degrades every facet of its characters’ humanity.

It is a skilful hand that Aronofsky wields over his four threads of steadily diverging plotlines, locating them all in a web of social relationships destined to be ripped apart. At the point that we meet these characters, the deterioration has already been set in motion, with split screens dividing widowed Sara Goldfarb from her drug-addicted son, Harry, who has taken to pawning her possessions for money. Between him, his girlfriend Marion, and his friend Tyrone, the three earn a small profit through dealing heroin, looking to fulfil their grand ambitions, or in the case of Tyrone, simply escaping from the ghetto. For Sara, success manifests not as financial wealth, but in the glamour of fame and beauty, and an invitation to appear on her favourite, mind-numbingly tacky game show ‘Juice by Tappy’ is the shove she needs to start losing weight with help of prescribed amphetamines.

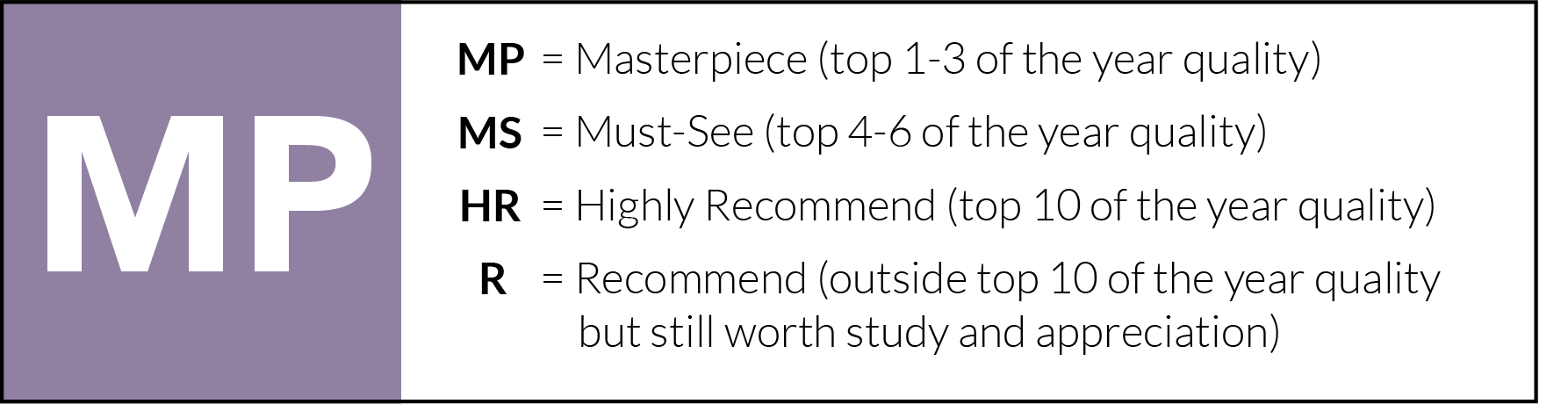

Aronofsky is economical with his social commentary, rejecting the sort of didactic expositing that a weaker filmmaker might have opted for, and instead embodying his critiques of the American Dream within the very fabric of characters who operate on either sides of the legal fence, and who are variably disadvantaged by some intersection of class, gender, age, and race. More than being some anthropological or ethical lecture, Requiem from a Dream is a panic-inducing trip, clouding our long-term vision of these characters’ arcs by over-sensitising us to the immediate impacts of each high. Every time heroin is injected, cocaine is snorted, or pills are swallowed, short, rhythmic montages deliver swift barrages of disturbing close-ups against black backgrounds, manifesting as a dark precursor to the rapid editing style Edgar Wright would trademark a few years later with Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz. Paired with these fleeting images are equally brief sound effects that amplify the volume of every movement a hundredfold, turning dilating pupils into rising electronic tones and rushing bloodstreams into intimate sighs, intoxicating us with pulsing, sensory overloads.

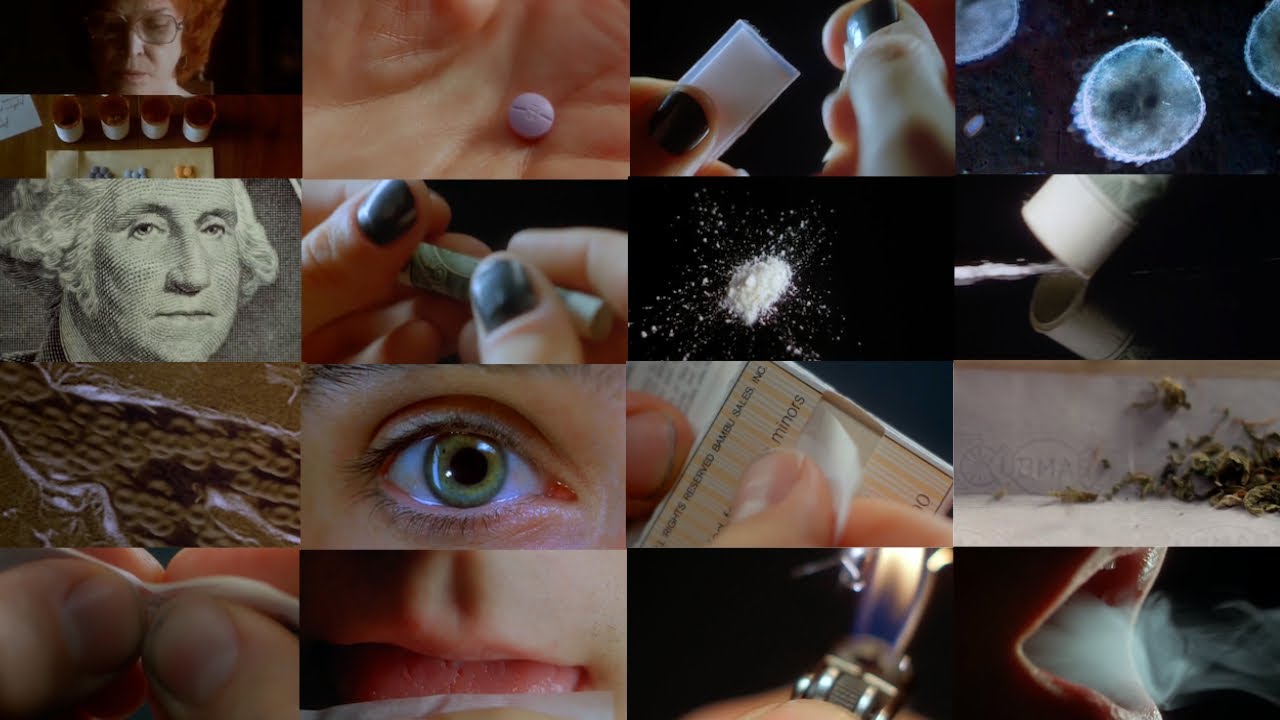

These mini-montages rarely last for more than a few seconds each, and yet they are ridden all through Requiem for a Dream, at times landing like punctuation marks in the middle of scenes. Each of these are imbued with great power, pivoting entire emotional journeys on the cathartic relief they provide. Harry’s emotional breakdown in the back of a taxi is easily forgotten in one scene when a quick flash of an injection wipes the anguish from his face in the very next shot, and Aronofsky goes on to extend this editing motif to the compulsive rush that Sara gets while watching her favourite television show. These fixes bring about feelings of elation for each character in their own way, turning jittery camera movements into dreamy glides circling dazed characters in overhead shots, divorced from any gravitational orientation.

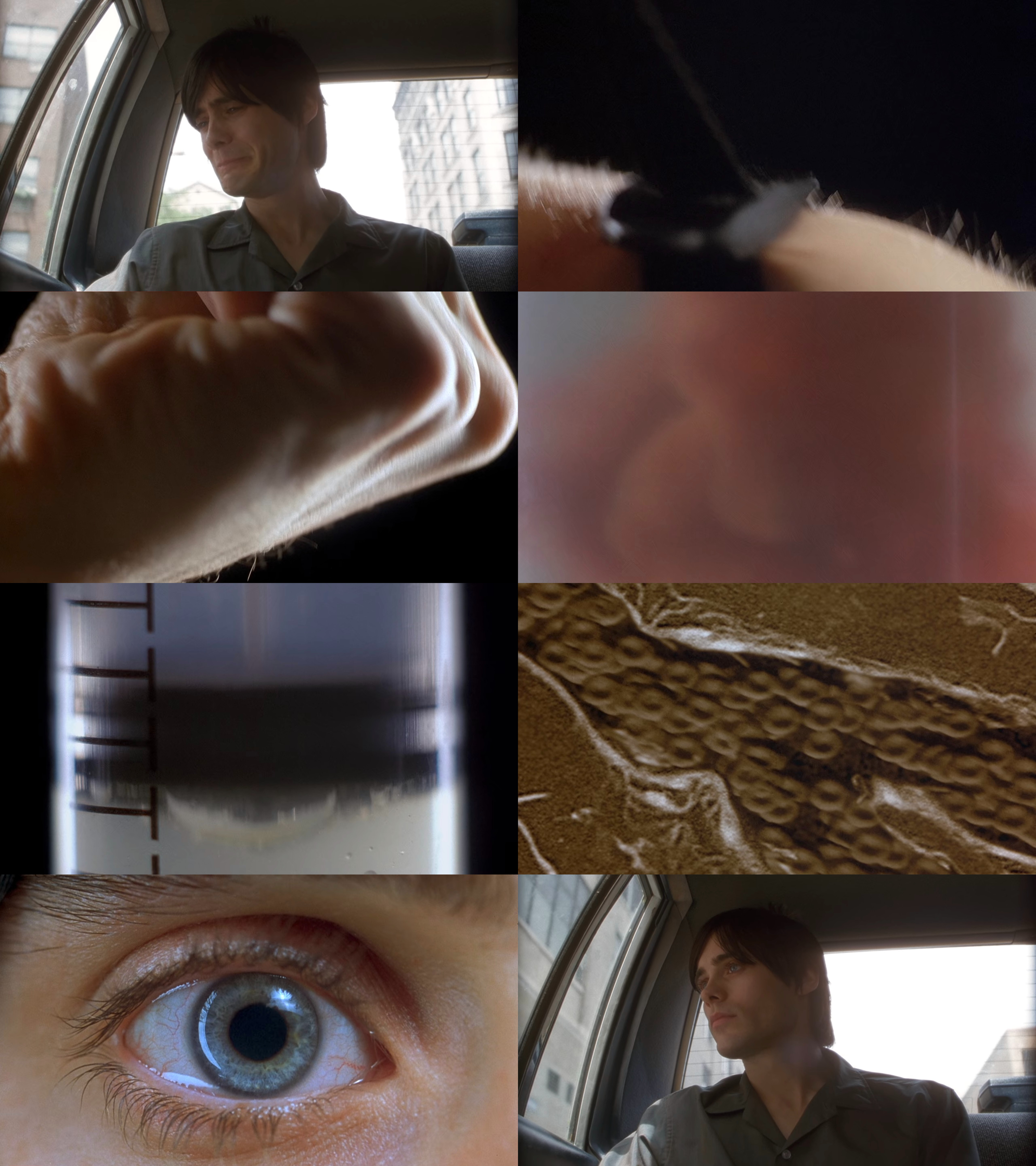

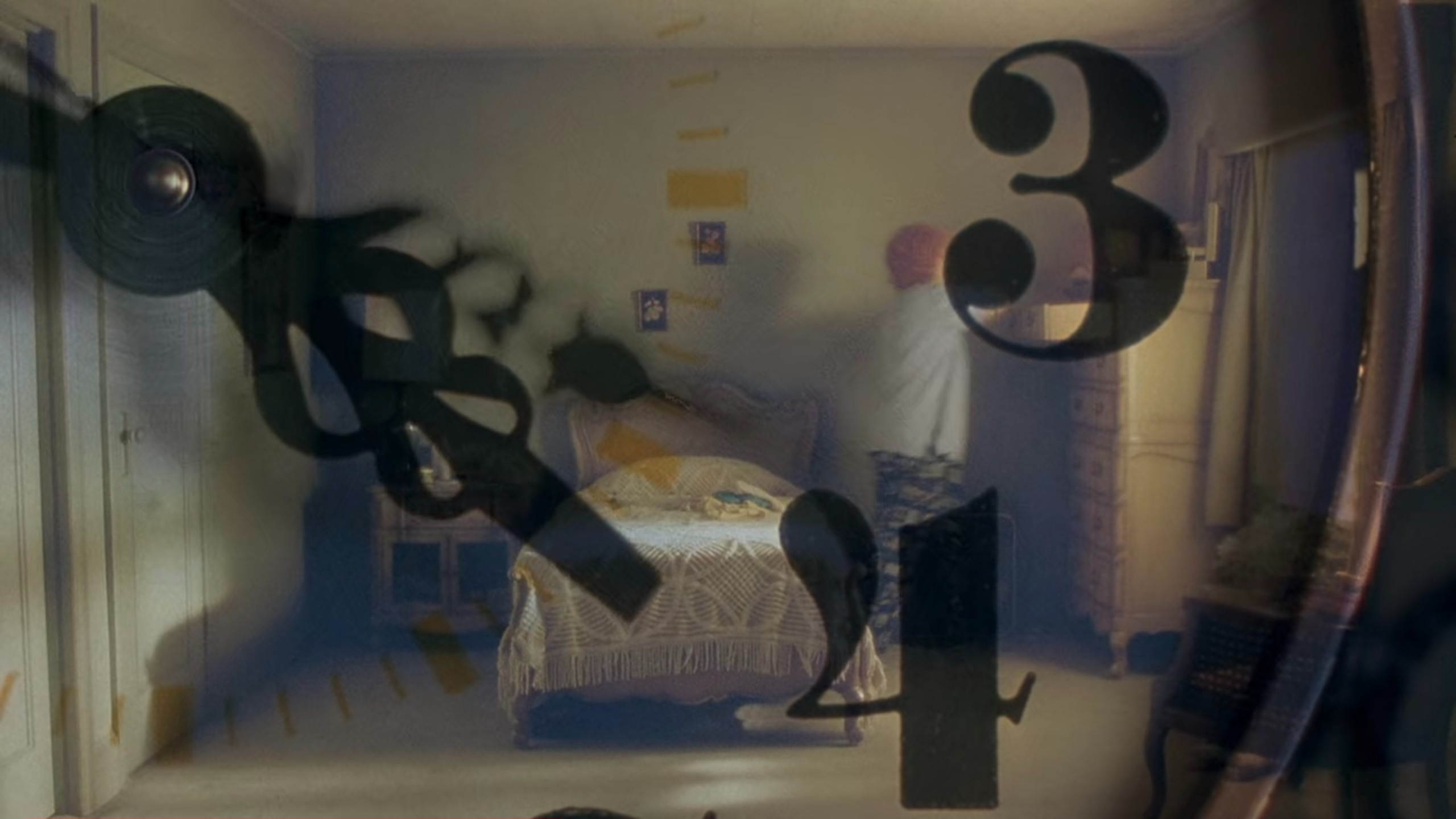

As the hallucinations of Aronofsky’s characters intensify, so too does his agitated visual style, slapping us with fish-eye lenses, time-lapse footage, reverse point-of-view tracking shots, and even one sequence that sees Sara experience the world in fast-motion while she can only speak in slow-motion. Time moves irregularly around these characters, and each member of the cast does remarkably well to keep up with Aronofsky’s deliberate erratic pacing, though it is especially in Ellen Burstyn’s upsetting descent into insanity that we pitifully regret the debasement of something innocent. The doctor who prescribes her medication is little more than a state-sanctioned drug dealer, caring so little for her that he doesn’t even make eye contact with his patients, and resolving to simply give pills to whoever asks for them. As the oldest of the four characters, Sara is the one who lives deepest in a pit of fragile insecurity, and it is hard not to feel an ache of sorrow for Burstyn as she delivers a monologue on the cheap, shallow joy these new drugs have brought her.

“I’m somebody now, Harry. Everybody likes me. Soon, millions of people will see me and they’ll all like me. I’ll tell them about you, and your father, how good he was to us. Remember? It’s a reason to get up in the morning. It’s a reason to lose weight, to fit in the red dress. It’s a reason to smile. It makes tomorrow all right.”

As despairingly delusional as Aronofsky’s characters have been up to this point, it isn’t until the final act that Requiem for a Dream fully sweeps us away on waves of surreal hopelessness, aggressively intercutting between each narrative thread driving towards what might as well be their graves. When Sara isn’t imagining television stars in her house or a monstrous fridge lurching towards her, she performs to her own mirror, with long dissolves melding several close-ups into a single deranged fantasy. Out in public, she draws pity and disdain from strangers as she raves maddeningly to herself, while elsewhere her son repulsively shoots up into an infected hole on his arm. When he and Tyrone are arrested, it is no surprise that it is the latter who is met with the full force of the law, being from a Black ghetto in New York, leaving Marion to fend for herself as a prostitute.

In a psychiatric ward, Sara undergoes agonising electroconvulsive therapy, and the hallucination of winning the television game show no longer seems to be just a side effect of her mental illness, as it also becomes an escape from her ugly reality. While she pictures the future she always wanted for her and Harry, she remains unaware that he is lying in a hospital elsewhere, getting his gangrenous arm amputated. Match cuts aggressively flow from one character to the next, with a close-up of a feeding tube being shoved into Sara’s mouth leading into Marion applying lipstick, and the torches that shine brightly on her vulnerable body at a sex party becoming hospital pen lights beaming invasively into the camera’s lens.

As each addict grows further apart, their stories intertwine even closer, and Aronofsky orchestrates his parallel editing to the agitated pulse of the titular requiem, with its strings and vocal chanting moving in circular rhythms like an angry, endless nightmare. Unlike traditional requiems which peacefully commemorate the souls of the deceased though, Clint Mansell’s score intensely evokes that mortal terror that immediately precedes death – or at least, the end of a life worth living. Within a mental health facility, a prison, a hospital, and a brothel, each character curls up into lonely fetal positions, lying in their final resting places. As Requiem for a Dream approaches its devastating climax in the final seconds, Aronofsky pessimistically conjures up a set of tragic fates worse than physical death, obliterating the souls of people who could see no other path to success in America than by transcending their biological limitations through destructive, mind and body altering substances.

Requiem for a Dream is currently streaming on Netflix and Stan, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

2 thoughts on “Requiem for a Dream (2000)”