CERN is an inspiration to people worldwide — not only scientists, researchers and engineers but students, children and their parents too. As I count myself as belonging to many of those categories, I’m always excited to hear the latest on CERN’s plans for the future. So with that as context, here’s my take on CERN FCC Week 2023 🙂

Looking to the Future: CERN FCC Week 2023

Last week I was in London for CERN FCC Week 2023, an event which brings together the people – scientists, engineers, researchers and more – working on CERN’s Future Circular Collider (FCC) project to present and discuss the latest details from the ongoing feasibility studies and planning assessments.

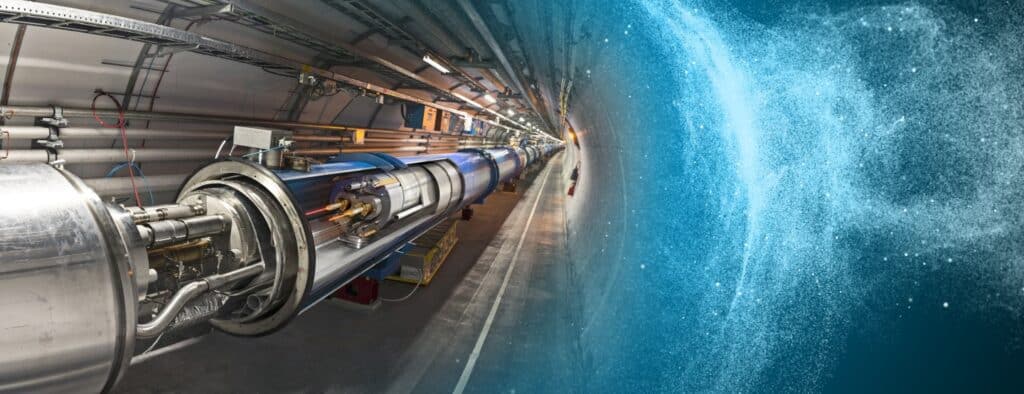

You’ve probably heard of CERN, which was founded in 1954, and may well have heard of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator, built underground and which forms part of CERN’s accelerator complex sitting astride the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva. The LHC started operation in 2008 and is arguably most famous for confirming the existence of the Higgs Boson, the discovery of which was announced by CERN on the 4th July 2012, 48 years after it first appeared in the scientific literature.

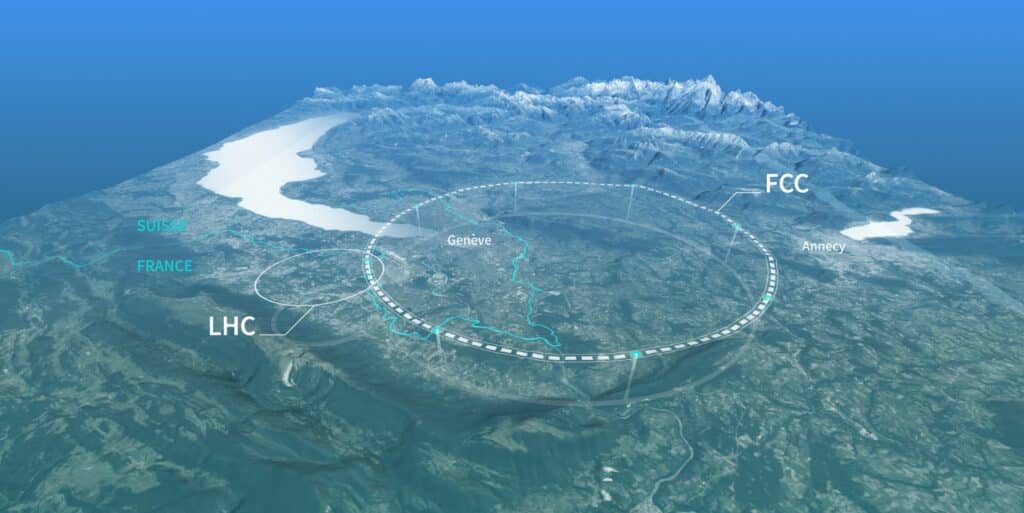

Ok, so that’s CERN and the LHC…so what’s the FCC? The FCC is the ambitious proposal to explore higher energy collisions in a new underground laboratory similar in principle to the LHC but at a larger scale; where the LHC is a 27km ring of superconducting magnets, the FCC ring would be approximately three times longer! The latest geological and civil engineering assessments suggest a collider circumference of 91km is feasible.

The timescales for operation of the FCC are not short; construction is not estimated to start until 2030, with first operation of FCC-ee (electron-positron collisions) slated for 2045, and first operation of FCC-hh (proton-proton collisions) in 2070.

It is this second stage of the FCC, FCC-hh, which is the 100 TeV hadron collider intended to push the energy frontier an order of magnitude higher than that of the LHC.

But before we get onto the FCC, and why it’s such a unique opportunity despite (or perhaps because of) the long timescale involved, it’s worth revisiting the LHC and that moment in 2012 from the perspective of someone who was there, namely Professor Jon Butterworth. Jon was a guest on the panel for the week’s main public engagement event, “Giant Experiments, Cosmic Questions” held on the 8th June at The Royal Society. The panel featured fellow particle physicist Dr Sarah Williams, alongside radio astronomer Professor Anna Scaife and gravitational wave astronomer Dr Laura Nuttall, and was hosted by the brilliant Robin Ince.

It was lovely to hear Jon’s brief retelling of the story of the discovery, and how those first few years of the LHC were the best and most exciting of his professional life. As a child he undertook the important task of writing a book about the planets and moons in our solar system, and recalls the need to continually update it as astronomers discovered new moons of the outer planets. These astronomers and their exploration of the solar system inspired Jon to become an explorer of physics on the microscopic scale (and beyond).

In his talk he makes the point that particle physics colliders are tools for exploring the universe, not simply “detectors” as they are often labelled. The collisions they generate provide a view on physics at the small scale in the same way telescopes (of all kinds) help us explore the early universe and physics on a much larger scale.

What does this have to do with the FCC, a particle physics collider? Well, in much the same way that we use telescopes such as JWST — and Hubble before it — along with radio astronomy telescopes such as the Square Kilometre Array to explore the universe looking outward, we use particle physics accelerators to look at small scales. As Jon put it in his talk, we are often in uncharted waters and don’t know what we’ll find until we look.

Jon spoke passionately of being inspired as a child by astronomers discovering new moons in the solar system – this gave him the aspiration to discover something new, to be an explorer, which led him to CERN and the LHC, where he (and others of course!) have inspired the next generation of early career researchers to continue to explore high energy physics to better understand the universe we live in.

This brings me nicely onto the Early Career Researchers (ECRs) session at CERN FCC Week. Hosted by Dr Sarah Williams — who I had the fortune of being seated next to at the conference dinner the evening before — it gave the panel of ECRs, including: Abraham Tishelman-Charny (Brookhaven National Laboratory), Andrey Abramov (CERN), Armin Ilg (University of Zurich), Emily Howling (Univ. of Oxford University College), Julia Gonski (Columbia University), and Tevong You (King’s College London), the chance to discuss their hopes, fears and experiences to date with the FCC project.

(as an aside, I’d also bumped into Armin at the conference dinner, where we briefly discussed Overleaf! His feature request was for push notifications to e.g. Slack, or at least the APIs to make that possible — something which is indeed on the long list, albeit not yet on the immediate roadmap. Still, there’s lots of cool new stuff coming soon 🙂)

After Sarah’s introduction, Armin and Julia both gave excellent presentations to kick things off, and each panellist then spoke very eloquently as to how they’d come to be involved in the FCC project. A theme that ran throughout their stories and the way they answered the questions from the audience was one of exploration and the desire to probe the boundaries of what’s possible — to be at the cutting edge of research, and to be part of the community making that happen.

There was also a notable degree of pragmatism; they all appreciated the complexities and challenges in getting a project such as FCC approved, and in their answers highlighted the successes and opportunities, ranging from the amazing support they’ve already seen from the local communities where the collider will be built, to the wider benefits of funding large scale projects that manifest themselves in many different ways throughout the life of a project such as this. And in spite of some of the concerns only natural with the project still in its early stages, the session had a real air of optimism and enthusiasm about it, and a hope for the future.

In my eyes, this represents the true success of CERN – not in the discoveries, but in the inspiration and excitement it generates in each new generation. And that is why, to me, their next laboratory to explore the unknown — Future Circular Collider — represents a unique and compelling opportunity.

Firstly, and as was discussed extensively during the week, the assessments show that the economic case is extremely well-founded – designing, building and installing the FCC adds significant value in many areas, from the jobs it creates to the skills it develops and hones in the people building it. And this is just one example. By any measure, there is a good economic case for building the FCC.

The main question around the FCC is then not the economic cost but the opportunity cost: there are always more experiments to build than you have the resources / support for, and you have to ask whether there is something else you could and/or should be focusing on.

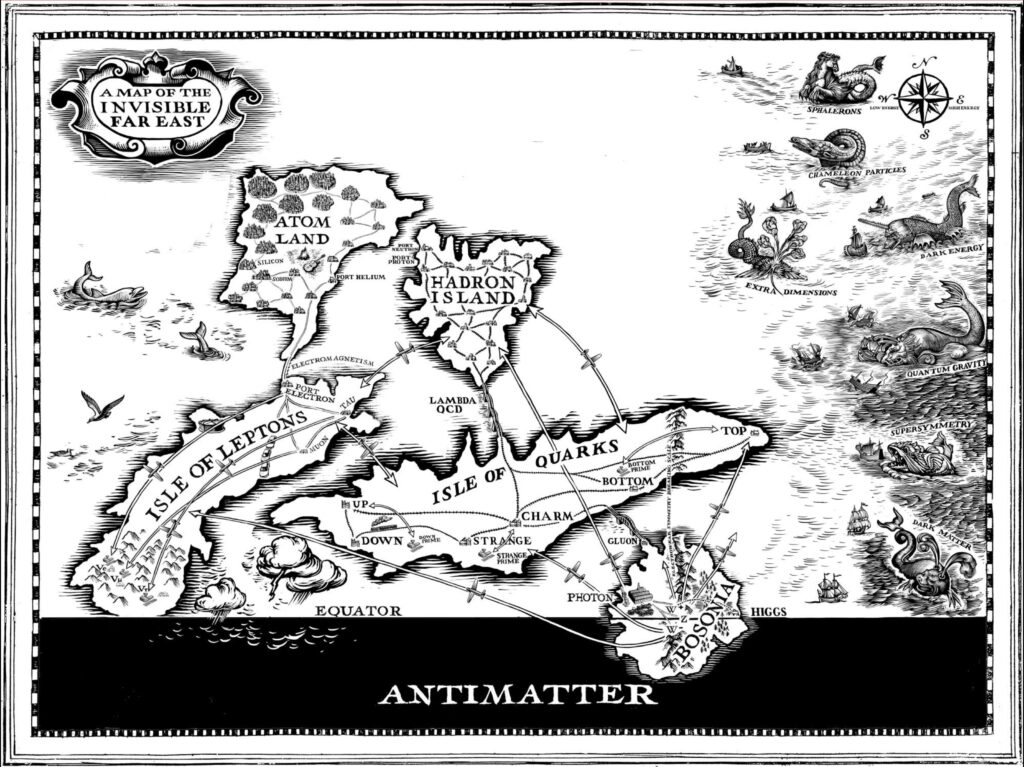

Arguments against the FCC make the case that the scientific and engineering resources it requires would be better spent elsewhere, especially given the long timeframe and scale of the project. There are also questions about whether the approach of building a larger collider like the FCC to explore higher energy collisions is the right one; essentially, will it be able to probe a large enough part of Jon’s map of the unknown to justify the (opportunity) cost.

But I don’t see this as a zero-sum decision; having the FCC as a flagship project will inspire more students (and perhaps more importantly, school children!) to become interested in physics and engineering, leading to more resources and more opportunities for other projects alongside the FCC.

Furthermore, CERN is one of the few organisations worldwide that can do this – it combines the ability to bring together an international community of scientists in a large-scale collaboration while at the same time being able to connect with the public in its educational outreach in a way perhaps second only to NASA.

CERN is a brilliant organisation whose scientists, researchers and engineers are exploring the boundaries of our understanding and, in doing so, are inspiring future generations to be explorers in their own way. That’s the real value of the FCC, and it’s a value that, to me, is hard to argue against.