The next Han Solo walks into a bowling alley on the edge of L. A.’s Koreatown, carrying a flip phone.

It’s a really nice flip phone. Top of the line. Looks like you could comfortably play Bejeweled on it for hours if you were stuck in an elevator in 2007. But this sort of dumbphone is also the most low-tech gadget you can carry while still being technically on-grid, which is how Alden Ehrenreich has come to prefer it lately. “I had an iPhone,” he says, “and then I’d forget my iPhone at home, and I’d be like, God, I feel so good. I’m having such a good day. And then I’d realize, Oh—it’s because I’m not checking my email nineteen thousand times.”

When he has the means to do that, Ehrenreich says, “I’m less able to be where I am, a little bit.”

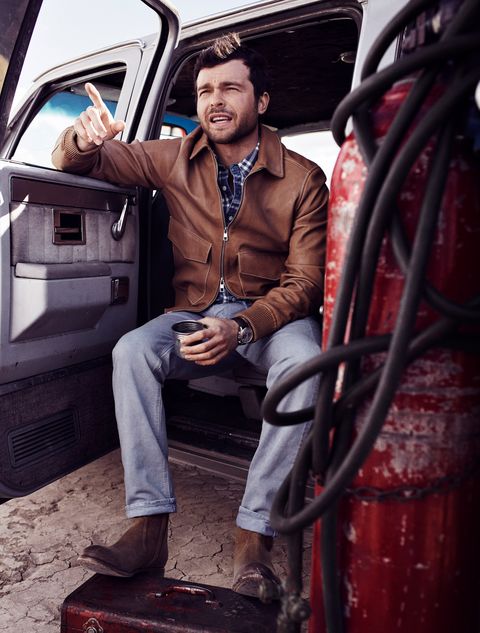

Today, smartphone-less and slightly more fully present, Ehrenreich finds a seat in the bowling alley’s otherwise empty sports bar and sips Diet Coke from a Styrofoam cup. He’s twenty-eight, but at the moment he looks younger, like an undergrad. Button-down western-cut shirt, windbreaker, utilitarian black hiking boots. A few days’ growth of beard softens his absurdly sharp jawline, knocks down the overall movie-star wattage of his resting face.

All told, he will hang out in this bowling alley for about three hours, and during that time he will be recognized and approached only twice—once by Justine, who is very sorry to interrupt but just wants to tell him that she loved him in the movie Beautiful Creatures (a 2013 YA-fantasy flop); and once by a skinny dude with a hipster mustache, who doesn’t really count because he recognizes Ehrenreich from NYU, where they took a class together on the history of the atomic bomb.

Nobody else bothers him. People tend not to when he drops by here, sometimes late at night, to shoot some pool or just observe the “real cross section of humanity” one sees in a bowling alley that stays open until three in the morning. All of that is about to change.

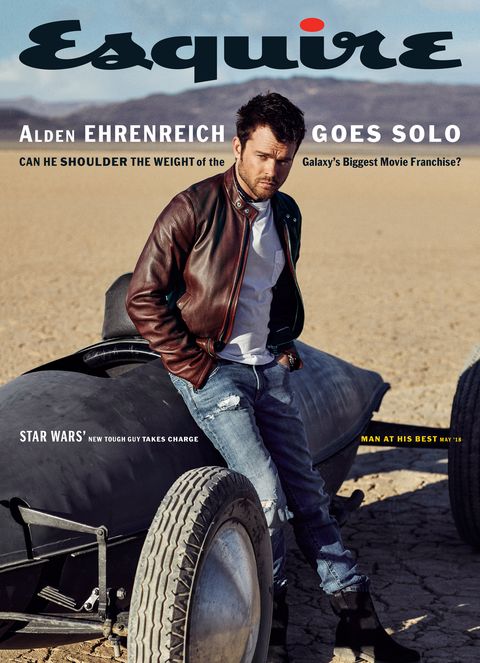

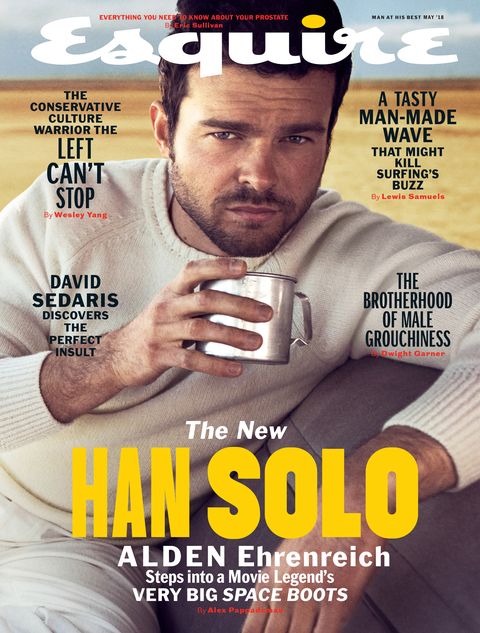

Solo: A Star Wars Story—starring Ehrenreich as a more callow version of a certain smuggler-turned-rebel-hero, with Donald Glover as Lando Calrissian and Woody Harrelson and Emilia Clarke as figures from Han’s life of crime—opens Memorial Day weekend. It marks the first time since the debut of the intergalactically maligned George Lucas prequels that we’ve been asked to accept a different actor playing a character introduced in A New Hope.

And not just any character—Han Solo, the closest thing Star Wars has to Bogart or Wolverine, the template for forty years’ worth of wisecracking- badass pop-culture icons, from Mal Reynolds on Joss Whedon’s cult series Firefly to Chris Pratt’s Peter Quill in Guardians of the Galaxy. Characters who wear their disdain for pomp and authority dangling off their gun belts, each channeling the inner five-year-old of a man who encountered Han Solo at the right age, nearly all of them missing the elusiveness of Harrison Ford’s Han, the way he seemed to drift through the franchise uncommitted, always ready to take the money and run.

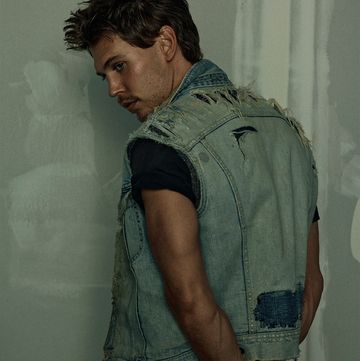

Ehrenreich is a millennial with the face of an old-school matinee idol who has yet to be thrown a pitch he can’t hit—operatic emotion for Francis Ford Coppola, Warren Beatty–esque sexy befuddlement for Warren Beatty, rope tricks for the Coen brothers. Physically, he’s enough of a Leonardo DiCaprio ringer to throw off facial- recognition software, and may have gotten the Han Solo role in part because Catch Me if You Can–era Leo wasn’t available.

So far, his best performance may be his funniest one—in Hail, Caesar!, for the Coens, as a dim-as-dust cowboy actor struggling with six words of drawing-room-comedy dialogue (“Would that it were so simple”) as if it were Sanskrit. He’s exhibited the kind of versatile talent that’ll allow him to shuttle, James Franco–style, from drama to dumbass and back, which will also likely come in handy as he juggles the varied tonalities of the Star Wars franchise’s first quasi-comedy.

Yet most of that work happened in films seen by few moviegoers and—probably—even fewer hardcore Star Wars fans. On the Internet, to which the actor has so carefully limited his access, the Why him? conversation won’t stop until opening weekend, and maybe not even then. But one way or another, he is writing himself into film history—for successfully reinventing a daunting pop-culture icon in his own image or for trying to do so and blowing it. Either way, by June, it’s doubtful he’ll be able to put his own name up on the scoreboard when he bowls.

When we meet, it’s March and nobody’s seen anything of Solo but the trailers. The first one starts with a growl of guitar distortion under the Lucasfilm logo and an unknown hand switching on the Millennium Falcon like it’s a Marshall stack. Within seconds, even before we get a glimpse of Ehrenreich with a canon-appropriate seventies shag, driving a landspeeder like he stole it, the point has been made—whereas 2015’s The Force Awakens gave us Ford’s Solo as a dad, this movie is about Han as a dude. And although Ehrenreich sought his predecessor’s guidance at a top-secret meeting before filming began, he doesn’t seem to be doing a Ford impression here.

From the looks of things, he’s found a more inside-out way to play the character: as a blustering rookie who already fronts like he’s the Han Solo but has yet to prove it to himself.

That quality is more or less what the film’s original directors, Phil Lord and Christopher Miller (who were replaced during filming by Ron Howard; more on that in a bit), were looking for when they set out to cast the role. “The outlaw thing is an act. We wanted someone who presented as a pirate but had a big heart underneath,” Lord tells me via email. “An impression of Harrison Ford would have felt like an extended Saturday Night Live sketch,” Miller adds. “We wanted someone who could evoke the spirit of the iconic performance we all remember while bringing something new and fresh. We talked a little bit about how Chris Pine, playing Captain Kirk, didn’t do a Shatner voice, and brought his own spin to the character while still evoking the vibe of the character. We felt Alden did the same with Han Solo.”

The directors say that Ehrenreich was literally the first actor they saw for Han, though they confirm rumors that they went on to audition upwards of three thousand. Kathleen Kennedy, the head of Lucasfilm, says the number was a somewhat less extravagant sixteen hundred but agrees that Ehrenreich stood out from “his very first screen test.”

“Alden, remarkably, remained the person to beat from day one,” Miller says. “We brought him in many times, pushed him, tried to test his range, and he was always up for it and brought something new, with a great sense of humor.”

“He felt classic and contemporary all at once,” says Lord. “He seemed like a tough guy who was really scared.” According to Kennedy, he also aced a key challenge: a screen test with Chewbacca.

Ehrenreich tells me he thought of the movie as “a biopic of a fictional character. Like when you watch La Vie en Rose or Walk the Line—you’re watching them become that thing. Or that scene in Chaplin when he goes into the wardrobe and finds the costume. That’s the feeling.”

“It’s not an ensemble war movie,” Howard says, “which is traditionally what they’ve been. It’s a rough-and-tumble rite-of- passage story about a young guy defining himself, and yearning for autonomy and being tested as an individual with his own agency for the first time.” Of course, that second sentence makes Solo sound, in spite of its intentions, an awful lot like a Star Wars movie. Howard—the two-time Oscar winner and card-carrying Friend of Lucasfilm—stepped in to direct Solo last July, after Lord and Miller were relieved of duty four months into production.

The duo, best known for comedies like 21 Jump Street and The Lego Movie, reportedly never saw eye to eye with the studio on the movie’s tone. There were rumors about poor time management, runaway improv, a let’s-find-it-in-the- edit approach you can’t get away with when your film is also a moving part in the machinery of a multibillion-dollar Disney franchise.

Of Lord and Miller, Ehrenreich says, “They had a different style than Ron in terms of the way we were working.” He’s not sure what their Solo would have been like. He liked the script. He liked them as directors. He can’t say whether they were really taking an Apatovian riffs-over-script approach. “From the first screen test on, we played around with it a lot. We tried a lot of different things, rethinking behind the scenes,” he says. “That was yielding a different movie than the other factions wanted. I knew what I was doing, but in terms of what that adds up to, you’re so in the dark as an actor. You don’t know what it’s shaping up to be, how they’re editing it, so it’s kind of impossible without having seen those things to know what the difference [of opinion] was, or exactly what created those differences.”

On any movie set, Ehrenreich says, regarding whatever arguments were going on between the directors and Lucasfilm, “the actors are at the kids’ table, unless you’re also a producer of the movie. So you’re really kept out of all the backroom dynamics of what was going on.”

He wasn’t told that Lord and Miller were being replaced until it happened, he says. The directors themselves told him almost immediately. “They said, ‘We were let go,’ and that’s it. They had mentioned there were some disagreements before, but they didn’t get into it. They wished me the best with the rest of the movie. On a personal level, it felt emotional, for them to be going after we’d set out on that course together. Because I spent a lot of time with them, and we had a really good relationship—they also cast me. But I think at that point, they were kind of on board with [the decision], too. Like, ‘This is what’s happening.’ That’s not what they said to me, but that was the vibe I got.”

Ehrenreich says the fan-press rumor that it was he who approached Kennedy with concerns about Lord and Miller is “not at all” true, that he couldn’t imagine ever making a call like that “unless people were being put in danger or something.”

He also insists that the story about Lucasfilm forcing Lord and Miller to bring in an acting coach—later identified as writer- director Maggie Kiley—to work on his performance has been mischaracterized: “She was part of conversations that happened for a couple weeks at one point,” Ehrenreich says, “but that was basically it.” (Lord and Miller say that Kiley is someone they’d worked with on previous films and that they brought her on Solo as a resource for the entire cast as well as themselves.) As for the various stories about the Solo crew breaking into spontaneous applause upon hearing of Howard’s appointment or (depending on which account you read) Lord and Miller’s firing?

“That’s bullshit,” Ehrenreich says. “For a crew to do that would mean they hated [Lord and Miller], which was not by any stretch the case.”

The production went dark for almost three weeks between Lord and Miller’s sacking and Howard’s arrival. “It was this period of going, What if they get somebody that you don’t get along with? What if they get somebody that has a totally different vision?” Ehrenreich admits. But he adds that Howard won over the cast and crew quickly.

“Everybody’s hackles are raised a bit, and Ron had this ability to come in and deal with morale and get everybody enthusiastic about, A, what we’d already shot, because I think his feeling was that a lot of what we’d already done was really good, and, B, the direction for the next piece of it. He knew how to navigate a tricky situation, and almost from the first or second day everybody pretty quickly recharged and got excited again about the movie.” (Lord and Miller ended up with executive-producer credits on the film. Everyone involved is cagey about how much of their material ended up in the final cut.)

You can tell Ehrenreich doesn’t particularly love talking about this stuff, but also that it’s a little frustrating to be sworn to secrecy about the movie and therefore unable to defend it from bad buzz in any non-vague way. But there’s one point he can make without spoiling anything, which is that Star Wars movies are always a little fucked up at first.

“I go back to the documentaries I watched about the making of A New Hope,” Ehrenreich says. “R2-D2’s falling apart, and they come back from the desert with, like, a quarter of what they needed to shoot. It’s kind of in the DNA of something this enormous to be a bit of a challenge.”

By the time Ehrenreich and I have reached the fifteen-minute mark of our acquaintanceship, he’s asked me where I grew up, where I went to college, when I decided to drop out, and why. I’ve been asked polite questions about myself by movie stars before and I know what it feels like. This isn’t that. Ehrenreich seems legitimately interested; he wants to connect.

And if he’s this way with someone like me, it’s suddenly easy to understand why—talent aside—all these world-class directors were drawn to him: He’s handsome enough to carry a movie but nerdily inquisitive enough to remind them of themselves. “He was reading the Sidney Lumet directing book, he was reading the Elia Kazan book on set,” Howard remembers. “I think he probably reads a book a day.”

“He’s a total sponge,” says Coppola, who cast Ehrenreich in 2009’s Tetro, the actor’s feature debut. “He wanted to know everything about New York in the sixties and seventies. Alden really loves to learn things, wherever he can.”

The things he gets excited about are, in general, things that would bore the pants off many young actors but would thrill the guy from the TCM-fan-club commercial who can’t believe he’s Skyping with Ben Mankiewicz: getting to watch a little bit of footage from Orson Welles’s unfinished The Other Side of the Wind when Kennedy’s husband and former producing partner, Frank Marshall, was assembling it as a Netflix movie; or sitting with Beatty, who directed him in 2016’s Rules Don’t Apply, and listening to Beatty talk about the notes he’d gotten on his script from Robert Towne and Aaron Sorkin and David Mamet and Elaine May. Ehrenreich actually got to spend some time with May, he says, “which was a dream”—he is a big fan of her 1976 film Mikey & Nicky, with John Cassavetes and Peter Falk as doomed wiseguys on the run.

“One of the things I remember Warren Beatty saying,” he tells me, “is that he had a conversation with Jodie Foster once about what the actual value of fame is. And she said this thing that he really liked, and that I really liked, which is that the main value for her was access. For me, to get to be around these people whose work I’ve admired, and ask them really specific questions about that work, is kind of amazing. That’s been the most fun thing—watching these movies growing up and then getting to say, like, Why’d you do this? Why’d you do that? What did you do here?”

Ehrenreich spent his childhood in Pacific Palisades, which he describes as being like a small town that happens to sit within the borders of Los Angeles. This is how you describe a wealthy enclave like the Palisades if it’s your wealthy enclave. His father died when he was just seven years old under tragic circumstances that he won’t discuss. His mother is an interior designer who loves movies. Their life together, Ehrenreich says, “was very much a conversation about art and aesthetics,” although he had to sneak off to his grandmother’s house to watch R-rated films like The Godfather.

He attended the arts-focused private school Crossroads, in Santa Monica, and haunted local revival theaters on weekends. Like a lot of budding cinephiles, he soon started making films of his own. “Me and my friend Gianni would make the silliest crap we could possibly think of, just to make ourselves laugh,” Ehrenreich says. “What you would do on YouTube now, basically.”

But he and Gianni knew this girl who was friends with one of Gianni’s cousins. They’d show her their dumb movies and she’d laugh. Eventually she asked them to make one she could screen at her bat mitzvah reception.

“So we went over to her house and filmed me chasing her around,” Ehrenreich says. “I’m in love with her, and I sing a song about her and she rejects me, and I cry and I eat dirt. Then there’s a time jump to ten years later, and she’s getting married, and I’m in a kimono, screaming.”

The video played on a loop at the party, and one of the guests was a family friend named Steven Spielberg. The director saw something in Ehrenreich that day—a willingness to go for it, for one thing. They didn’t meet, though, because—and this is the best part of the story— Ehrenreich wasn’t at the bat mitzvah. He was away at a Latin-club event. Yes, Latin club.

“I remember these girls calling me and giggling and saying something about Spielberg being [at the party],” Ehrenreich says. “I thought it was just a prank call. And then Leslee Feldman, who was the head of casting at DreamWorks, called my mom.”

Ehrenreich got an agent based on that conversation. Then, for a few years, he got nothing else, until one meeting, with producer and longtime casting guru Fred Roos, led to another meeting, with Roos’s longtime collaborator Francis Ford Coppola, who was looking for a real eighteen-year-old to play the eighteen-year-old protagonist of his next movie, a coming-of-age drama set in Argentina called Tetro.

Coppola says he saw half a dozen actors for the role. “It’s just like in life—you might go to a party or an event, but the next day one or two people just stick in your mind for some reason,” he says. “Either they impressed you well or they impressed you badly, but you can’t get them out of your head. That’s usually an indication that that’s the person to cast. And so it was with Alden—he had qualities that seemed to last with you.”

At this point, the bowling-alley bartender puts on 2 Chainz and Drake’s “No Lie” and cranks it up, like he’s determined to get something started even though it’s three in the afternoon and we’re the only people here. Ehrenreich looks down with concern as my tape recorder starts to red-line.

“There’s other places we can go. There’s a Sizzler across the street,” he says, with the air of someone who is not unfamiliar with the Sizzler across the street. Instead, we find seats in a different corner of the bowling alley, across from a little coffee counter that looks like it’s been waiting undisturbed for its next customer since approximately 1964.

“I remember hearing this thing Orson Welles said about getting successful really young,” Ehrenreich continues. “He said, ‘It’s a bit like Wile E. Coyote—you run off the cliff, and you don’t even realize you’re off the cliff until you look down.’

“And this”—shooting Tetro with Coppola in Buenos Aires, he means—“was before I looked down. It was just such a romantic, exciting thing to me, to be there.”

Imagine: One day you’re in high school. (It’s a fancy high school full of show-business scions, but still.) The next, you’re standing in Francis Ford Coppola’s vineyard in Napa, screen-testing for your first feature. And then you’re living on your own in an apartment in a foreign city at eighteen, starring in a movie for the first time. The shoot itself is so immersive you don’t know if you’re on or off set, talking about art or acting in a movie about talking about art, waking or dreaming.

I suggest to Ehrenreich that Tetro is the sort of experience that could spoil you for a lot of the other kinds of work a working actor has to do.

“Sure,” he says. “Yeah, I know. I know.”

This is early in our conversation, when we haven’t talked much about Star Wars yet, but suddenly it’s the bantha in the room. I flash on something Coppola told me when we talked a few days earlier, when I asked him how he thought Ehrenreich would do as Han Solo, given the way these projects tend to take over an actor’s life. “If he’s going to be stuck playing one part, he’s going to have to just constantly learn to reinvent and bring new colors to it that can interest him,” Coppola had said. “Because I don’t think he’s the kind of person who’s just going to go in to work and collect the check and go home.”

After Tetro, Ehrenreich went to NYU for almost four years. Transferred after a semester from Tisch to the university’s make-your-own-major Gallatin School. Started a little theater collective with some friends, just so he’d have a venue in which to act and direct. In his spare time, he saw a lot of movies at Film Forum—a West Village institution that screens indies and revivals—and drank at a lot of people’s apartments. He didn’t tell anyone he’d just shot a Francis Ford Coppola movie until Tetro came out. He mostly let his film career sit idle. “I was still auditioning when I was in college,” he says, “but I wasn’t really giving it the old college try. I was giving college the old college try.”

Two things happened while he was in college, though: Tetro was released—to decent reviews if little box office—and Ehrenreich was introduced to Warren Beatty. The actor-director-screenwriter was finally gearing up to make Rules Don’t Apply, a Howard Hughes film he’d been tinkering with on and off since the mid-seventies; he wanted Ehrenreich for the role of Frank Forbes, a chauffeur in Hughes’s employ who falls for a starlet (Lily Collins) under contract to the mogul’s film company, RKO. “I think the first meeting I had with him was four hours,” Ehrenreich says.

Most of it involved him asking Beatty questions, he adds. “Warren occupies this very singular space of having been in old Hollywood, and knowing people Francis didn’t. He knew Kazan”—who had directed Beatty in his first film, 1961’s Splendor in the Grass. “So it was really cool to hear those stories, about Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor or John Wayne or Bette Davis. Those were all people Warren knew.”

For five years, Beatty tried to secure financing that would allow him to make the movie with Ehrenreich rather than a higher-profile actor. Shia LaBeouf, Andrew Garfield, and Justin Timberlake were reportedly all in the mix for Frank Forbes, and Ehrenreich says he always assumed there was a chance Beatty would throw him over for a bigger name.

“He wasn’t saying that,” he says, “but you’d find out that he was meeting with everybody else, y’know?”

Still, they’d talk all day at Beatty’s house. Or on the phone at night—Ehrenreich got those calls Pauline Kael got, the Beatty seduction calls. Ehrenreich had left NYU—he remains a few credits shy of a degree—and returned to L. A. to get back to acting. He started another little theater group, just to keep busy between auditions, and sometimes Beatty and Annette Bening would come see his plays. “They’d be in the audience of some little rat-hole theater,” he says, “and then take me out to dinner after.

“Honestly,” he goes on, “it was the only

really exciting game in town for me at that time. Outside of being with [Beatty], I was struggling to get into any kind of movie. My rank at the time was not great. So I was hanging in there, like, I sure hope this gets made. A lot of people told me not to. A lot of people told me it was never going to get made. I didn’t know. Warren would say, We’re gonna go now, and then that day would come and go. He has a very deliberate, slow process.”

Ehrenreich understands, at least a little bit, what’s happening when he plays a young Coppola figure or assumes a Beatty-esque role in a Beatty film—the transference that occurs, the way he’s both a performer and an onscreen surrogate, the way in which these guys can feel themselves living on through an heir.

We’re back at the question of rarefied air. Ehrenreich knows he can’t spend his entire career “frolicking in that world of film from the past,” that at some point, having apprenticed in a bubble where it’s still the seventies, he needs to figure out how to do the work the way the work is done, here in 2018. “Because that’s the only way in which these lessons become of value,” he says. “When they’re translated into what I do now.”

At one point while we’re talking, Ehrenreich stops midsentence and notices something that I’ve also just noticed.

“Are they...playing the Star Wars theme?” he asks.

We start looking around and realize we’ve been sitting this entire time maybe thirty feet from a pair of Star Wars pinball machines, one of which prominently features Harrison Ford’s face. The noise from the lanes has subsided a little, and now we can hear the stirring strains of John Williams’s title theme underscoring PA announcements about who needs a fresh ball on which lane. Ehrenreich laughs.

He was born in 1989, which technically makes him part of the Prequels Generation. He says he doesn’t remember ever jumping off furniture pretending to be Liam Neeson as Qui-Gon Jinn. (Does anybody?) But he has one prequel story to tell. In 1999, Ehrenreich got to attend an advance screening of Episode I: The Phantom Menace. He brought an autograph book, expecting celebrities; the only one who showed up was Shaquille O’Neal, which for Ehrenreich, a Lakers fan, was a big deal.

Growing up, he had an action figure of Shaq as the DC Comics hero Steel. As a professional, he’s gotten the chance to work with two actors—George Clooney in Hail, Caesar! and Val Kilmer in Coppola’s Twixt—whose Batman action figures he once owned as well. I ask him what it’s like to know that there will be a Han Solo figure out there with his face on it, that he’s now part of a franchise that will outlive him. It’s an impossible question for him to answer, and when he answers it, he endears himself to me forever by quoting Lester Bangs’s 1977 obituary for Elvis Presley, which doubled as a eulogy for the community bred by shared reverence.

“At the end of it, Bangs is like, ‘We’re not gonna ever have this again, so instead of saying goodbye to Elvis, I’ll say goodbye to you,’ ” Ehrenreich says.

“The world we live in now, everything is so niche,” he continues. “One of the beautiful things about being a part of Star Wars is that it’s one of those few things that are community- building in that way. Maybe that way of putting it is a little self-important. But it is something we all have a connection to, something everybody knows about. There aren’t that many of those things.”

We meet for the second time at Jones, a tiny checkered-tablecloth Italian place. Since we last talked, the Oscars happened. Mark Hamill, Oscar Isaac, and BB-8 were all there, representing the franchise. Ehrenreich wasn’t. Over iced tea and burrata—it’s the middle of the afternoon, so neither of us can decide which meal we’re supposed to be having—I ask him how his Oscar night went.

“I went to an escape room,” he says.

Make your own metaphor out of this, if you choose to. We talk about his meeting with Harrison Ford, which took place during preproduction on Solo. “I kind of raised my hand a little bit,” he says, “and said, ‘Let’s reach out.’ Because I thought it seemed right, to reach out to him.”

So Ehrenreich drove out to Santa Monica airport, where Ford keeps his truly impressive collection of airplanes. The younger actor knew the history of Ford’s up-and- down relationship with the franchise. Ford had unsuccessfully lobbied for Lucas to kill off Han Solo in Return of the Jedi. He wouldn’t get his wish until The Force Awakens, and he refused to sentimentalize the moment even then. The New York Times asked if he thought of his return as a passing of the torch. “I don’t know that I thought of it that way at all,” he said. “I was there to die. And I didn’t really give a rat’s ass who got my sword.”

Ehrenreich confesses that he was intimidated sitting down with Ford because “you never know what to expect from people. And he was gracious and supportive and very welcoming—a real gentleman. I don’t think he was following the project that closely. He was just kind of like, ‘Hey, what’s up, kid?’ My impression is that when he did Force Awakens he was surprised at what a good time he had, and how meaningful it ended up feeling to him.”

Not that they talked about that, of course. They mostly talked about Coppola and Fred Roos—the kind of stuff Ehrenreich is interested in. Regarding Han Solo, he will only quote what the original nerf herder himself advised him to say: “Tell them that I told you everything that you needed to know, and that you’re not allowed to tell anyone.”

This sounds a lot like a meeting at which nothing happened.

“He admitted that he was more forthcoming with me than he was with Alden, because he didn’t want to hamstring Alden,” says Howard, who spoke with Ford after taking over Solo. “He thought it was so important that Alden find a character, within the scripted Han Solo, that he could connect with and understand, and not be limited by his advice in any way.”

At Jones, I ask Ehrenreich if it’s possible to go Day-Lewis deep on a character like this. “It’s easier than you’d think,” he says, “because there’s so much information on Star Wars. I did a movie about the Iraq War right before this, and there’s almost as much information about Star Wars.”

He delved into Wookieepedia, a fan- curated online reference source that’s exactly what it sounds like. He likes the idea that everything the characters do in this film, every place they visit, will become part of the lexicon. They’re writing directly into the canon. “The wardrobe is a big part,” he says. “I remember doing my audition on the Falcon, putting on the jeans with the Corellian bloodstripe”—per Wookieepedia, “an award for conspicuous gallantry given by the Corellian military forces”—“and thinking, Oh, yeah. This is Star Wars. Like, this really is Star Wars now.”

That near-three-week period between Lord and Miller’s firing and Howard’s arrival—well, of course it wasn’t fun. But it wasn’t a dark night of the soul, either. The questions it might have prompted Ehrenreich to ask himself, while waiting for word on who would be directing the rest of his movie, were questions he’d asked himself already, during a trip he’d taken in the middle of the audition process.

“Like as much as it’s”—and here he pauses and leaves a space, as if the various things that “it” represents were too huge and too obvious to name with actual words—“it’s also a decision you want to make sure you’re making of your own volition, and not just because everyone would think you’re insane if you didn’t. . . You don’t wanna get there and go, God, maybe I just did this because my agent told me to.” He knows what he’s getting into. It’s a deeper commitment than just one movie. Even Ford couldn’t quit after just one. I ask Ehrenreich how many he’s signed up for.

“Three,” he says, then flinches, understanding he may have just created a disturbance in the Force. “I don’t know if that’s officially, uh, public. But—yeah.” Anyway: Between auditions for Solo, Ehrenreich took a trip out to Death Valley. “I stayed in, like, a high-end tepee, which you can rent out there,” he says. “I’m making myself sound a lot more rugged than I actually am. I’m also getting green juices delivered to the tepee.”

It was when the “super bloom” happened—a once-in-a-decade explosion of Easter-bright flowers bursting to life in the desert. Evening primrose, brittlebush, gravel ghost. This was where Ehrenreich decided he’d be Han Solo, if they’d have him.

It’s only later that I realize he never quite told me why he made the decision. He does tell me he keeps a picture on his computer of a kid dressed as Han Solo posing with a dog dressed as Chewbacca—a quiet reminder of whom these movies are really for at the end of the day. A generation of kids will grow up with Ehrenreich as their idea of Han Solo, which, per Lester Bangs, is basically like being Elvis to a bunch of five-year-olds.

Maybe that’s a trap, and maybe it isn’t. Along with Solo and J. J. Abrams’s return to the franchise with the as-yet-untitled Episode IX (due in December 2019), the next few years will supposedly bring new multi-episode Star Wars sagas from The Last Jedi’s Rian Johnson and Game of Thrones’s David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, plus a live-action TV series overseen by Iron Man’s Jon Favreau. We are nearing an event horizon—not peak Star Wars, necessarily, but maybe the point at which being in a Star Wars movie becomes just a thing that happens to every working actor eventually and is therefore unremarkable, neither a Golden Ticket nor a death sentence.

In the end, Ehrenreich may be the best person for this job because he already sees it that way. He knows he can play Han Solo his way and he knows that there’s nothing he can do to change or even predict what will happen once he’s done that.

“You can control your decision to say yes, and you can control your own work, the work you put into it,” he says. “And you can control how you treat people. And”—he laughs—“that’s about it...In a way, walking a tightrope that’s a lot higher is a great way to learn that lesson more profoundly.”