To many, 1941’s Citizen Kane—with its spiraling narrative, dramatic use of close up and lighting and not-so-subtle commentary on the media tycoon William Randolph Hearst—is often considered the best movie of all time. The film is synonymous with its director, star, and co-writer, Orson Welles. The rave reviews that poured out when it was released in 1941, and subsequent celebration by critics in the decades following, helped cement Welles as one of America’s greatest auteurs. The fact that he created Citizen Kane at age 24 will make even the most over-achieving overachiever weep.

But there's one question that has been percolating among a small subset of film nerds since the '50s: was Welles really the sole artistic tour-de-force behind Citizen Kane?

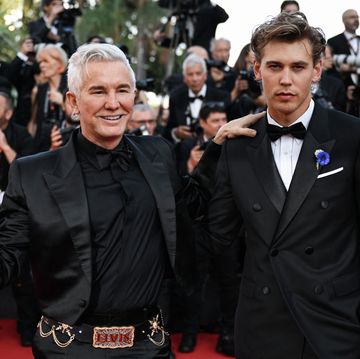

The question of who was the real genius behind Kane bubbles up in a big way in the Academy Award nominated Mank, the David Fincher film that began streaming on Netflix on December 4. It is the story of Herman J. Mankiewicz (Oscar nominee Gary Oldman) aka Mank, the other person behind the screenplay of Citizen Kane. In fact, Mankiewicz, along with Welles, would share the sole Oscar awarded to the film: Best Original Screenplay.

So how accurate was Fincher’s portrayal of the actual Mank? In the film he’s depicted as someone with near-Shakespearen levels of writing ability and the life of the party who was bogged down by personal issues (alcohol, money, family). And beneath it all, however, resided a strong moral compass. Unlike Charlie Kaufman’s neurotic character in Adpatation, another Hollywood movie about a screenwriter with huge bouts of writer’s block, you sort of want to be Mank—at least at the times where he exudes charm and wit with ease at social gatherings and partying at the sprawling Hearst Castle in San Simeon. (Minus one scene at the Castle towards the end. You’ll know it.) You root for him, but wish he could just put his glass down every once in a while.

In real life, Mank was pretty much that, according to most reports. He was the first theater critic for The New Yorker, before becoming the head of Paramount’s scenario department (basically the studio’s writer’s room depicted in Mank as very smoky, and very male, save the secretaries). Prior to Citizen Kane, his most notable contribution would probably be his work on The Wizard of Oz.

As a member of Algonquin Round Table, he moved easily among social elites, including William Randolph Hearst and his mistress Marion Davies portrayed by Charles Dance and Amanda Seyfried, respectively.

Where Mank takes the most liberties with Mankiewicz’s story is his support of socialism and Upton Sinclair. In the film, Mankiewicz is screened a fake newsreel produced by a director friend designed to torpedo Sinclair’s chances in the upcoming election versus the conservative candidate Frank Merriman who was backed by studio heads and William Randolph Hearst. It’s this film, a kind of fake news and a perverse use of the medium of film, where Mankewicz decides to really double down on turning against Hearst and Louis B. Mayer and create Citizen Kane’s Charles Foster Kane as a scathing critique of the media tycoon and his world.

So did Mank actually write all of Citizen Kane as the movie portrays? While Mank mostly dives into the relationship between Mankiewicz and Hearst, the large undercurrent of the film gets into the idea that Mankiewicz deserved more credit for Kane than he has received over the years. This idea was actually first brought forth in a big way by one of The New Yorker’s film critics, Pauline Kael in 1971 in a 50,000 word story entitled “Raising Kane.” As Kael posits early in her article:

[Welles] has never again worked on a subject with the immediacy and impact of “Kane.” His later films—even those he has so painfully struggled to finance out of his earnings as an actor—haven’t been conceived in terms of daring modern subjects that excite us, as the very idea of “Kane” excited us. This particular kind of journalist’s sense of what would be a scandal as well as a great subject, and the ability to write it, belonged not to Welles but to his now almost forgotten associate Herman J. Mankiewicz, who wrote the script, and who inadvertently destroyed the picture’s chances. There is a theme that is submerged in much of “Citizen Kane” but that comes to the surface now and then, and it’s the linking life story of Hearst and of Mankiewicz and of Welles—the story of how brilliantly gifted men who seem to have everything it takes to do what they want to do are defeated. It’s the story of how heroes become comedians and con artists.

A year later, in the pages of Esquire, Peter Bogdonavich would go on to refute this idea in a story called “The Kane Mutiny.” The big omission from Kael’s story—she never bothered to interview Orson Welles about the issue of credit, even though he was very much alive then. (Fun fact, Orson Welles’ final role was as Unicron in Transformers the Movie in 1986.)

Bogdanovich interviews screenwriter Charles Lederer, a close friend of Mankiewicz’s in the Esquire story. Here’s the key passage:

Contrary to what Miss Kael would have us believe, Mankiewicz was more than a little concerned about the Welles version of the screenplay. Charles Lederer, one of the best and wittiest of screenwriters, and an intimate friend of Mankiewicz’s, described it to me: “Manky was always complaining and sighing about Orson’s changes. And I heard from Benny [Hecht] too, that Manky was terribly upset. But, you see, Manky was a great paragrapher—he wasn’t really a picture writer. I read his script of the film—the long one called American—before Orson really got to changing it and making his version of it—and I thought it was pretty dull.”

So did Mank deserve the credit he got for writing Citizen Kane? Definitely. But so did Welles apparently. But somewhere in between those two claims is the truth, and also movie magic.