The quest for the Holy Grail began long before King Arthur

King Arthur is the most famous figure to seek the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper, but others came before him—and their tales are as ornate as the object itself.

The Holy Grail has occupied a central place in the Western imagination for millennia, whether as a sacred relic, a lost treasure, or an object of unattainable perfection. But the Grail did not begin as any of those things. Rather it was a simple cup at the Last Supper. The earliest reference to it can be found in Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, the basis of the sacrament of the Eucharist. Written around A.D. 53, Paul’s words are heard every Sunday by many Christian worshippers around the world: “In the same way, after supper he took the cup, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me’” (1 Corinthians 11:25).

The Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke also describe how the soon-to-be crucified Jesus bids his disciples to drink wine from a cup as a communal ritual. (The Gospel of John makes no mention of it.) The oldest Gospel account of the Last Supper is that of Mark, written sometime after Paul’s epistle but before the destruction of the Jewish Temple in A.D. 70. The later Gospels of Matthew and Luke also present the key elements of Mark’s account.

(How did Jesus' final days unfold? Scholars are still debating.)

As Christianity grew and spread, the miraculous process by which bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ developed into the doctrine of transubstantiation. This belief was widespread in Christian Europe by the 12th century, and the vessels that were part of these Holy Communion ceremonies became venerated themselves. It was around this time that the original cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper began to appear in literature. Dubbed the Holy Grail, the cup’s whereabouts, protectors, and powers were a favorite topic of medieval authors. The search for the Grail and the contest to possess it became the basis for a rich tradition of literature and storytelling that would last for centuries.

Rise of relics

The fate of the original chalice from the Last Supper is unknown, but relics associated with Jesus began to surface shortly after the Roman emperor Constantine I converted to Christianity. His mother, Helena, was a Christian herself and believed to be instrumental in her son’s conversion. Around the year 325, shortly after the religion was recognized by the Roman Empire, Helena (later canonized as a saint) made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in search of early Christian relics and sacred sites.

(A black market for holy relics thrived in the Middle Ages.)

Among the stops on her tour was Jerusalem, but the city no longer resembled the one when Jesus lived. Roman legions had razed the city in A.D. 70 following the brutal suppression of a rebellion in Judea. Decades later, this time under the leadership of Hadrian, they again ravaged the city in 135 to crush a new revolt led by Bar Kokhba.

Helena was undeterred in her identification and mapping of holy sites. She had the invaluable help of Eusebius of Caesarea, a bishop and historian from Palestine whose Ecclesiastical History laid the foundations for the official history of Christianity. As a result of their “archaeological” investigations, specific places began to be associated with events surrounding the life and death of Jesus as described in the Bible.

Helena is credited with finding several relics, most notably the True Cross on which Jesus was crucified. Other items associated with her pilgrimage were a nail from the Crucifixion and the seamless robe Jesus wore on the cross. Helena also identified the tomb where Jesus was buried, the future site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built on Roman orders.

From that point on, relics would play a fundamental role in Christian worship, especially those related to the Passion, such as the Crown of Thorns, the Holy Lance that pierced Jesus’ side, and the Holy Sponge used to moisten Jesus’ lips during his suffering. Of all the objects associated with Christ, the chalice used at the Last Supper would prove the most elusive.

Chalice contenders

The first mention of the existence of an actual Grail relic comes in 570 in the form of an anonymous travelogue to the Holy Land, written by a man scholars call the pilgrim of Piacenza. In Jerusalem he saw “the sponge and the reed, about which we read in the Gospel; we drank water from this sponge. There is also the onyx cup which He blessed at the [last] supper, and many other wonders.” Over the next few centuries, references to the chalice dwindled considerably, even as veneration of relics increased in medieval Europe.

(How Jesus's childhood influenced the Gospels.)

The Spanish Cup

If viewed from a certain angle, the Chalice of Valencia’s inscription does indeed seem to disappear.

That’s not to say there were no objects believed to be the Holy Grail. Hundreds of goblets in churches, cathedrals, and monasteries across Europe have been candidates at different times in history. Among the most famous is a red agate vessel known as the Chalice of Valencia. The artifact came to prominence in medieval Spain; since 1399 it has been housed at the Valencia Cathedral, where it can be seen today.

Another contender is the Sacro Catino (the Holy Bowl), an octagonal green-glass container shaped more like a basin than a wine cup. Held today at the Treasury of the Cathedral of San Lorenzo in Genoa, Italy, it was supposedly found near Lake Galilee and brought to Genoa following the First Crusade in the 12th century. Studies conducted centuries later put the bowl’s creation after the time of Christ, although scholars still debate the exact date.

Royal quest

Around the same time that these chalices began drawing attention, literature also began focusing on the vessel and centering epic stories around it. The Holy Grail, as it would become known, was taking its place as one of the most precious and desired objects in all of Christendom.

The word “grail” itself is pregnant with meaning and mystery, with deep Christian connotations. Two etymologies are cited for the word. Its most likely origin is the medieval Latin gradalis, meaning “dish.” But an alternative explanation is that it derives from the Old French sang real, meaning “royal blood.”

In the course of the following centuries, Grail motifs and the quest to find the relic were woven into various stories, most notably those surrounding a legendary sixth-century leader who lived very far away from the Holy Land: Arthur, King of the Britons. Arthur’s story had been around in Welsh and English folklore for centuries, but his narrative began to solidify in 1136 when English bishop Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote an almost entirely fictional chronicle called History of the Kings of Britain. In it he expanded the early Arthurian legends. Back in the ninth century, Welsh historian Nennius had written, or at least compiled, a history of the Britons that included Arthur, but it was Geoffrey who first styled Arthur as the archetypal hero.

(What does the truth behind Excalibur and these other mystical historic objects reveal?)

Wace, an Anglo-Norman poet in the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine, wrote a verse chronicle, Roman de Brut—Romance of Brutus, in 1155, based on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s text. Wace described how Arthur came to power thanks to the magical sword Excalibur and founded the Knights of the Round Table. In the years that followed, the splendid court of Aquitaine, a kingdom in what is now France, provided fertile ground for troubadours and scribes to compose works featuring King Arthur, his knights, and the Holy Grail.

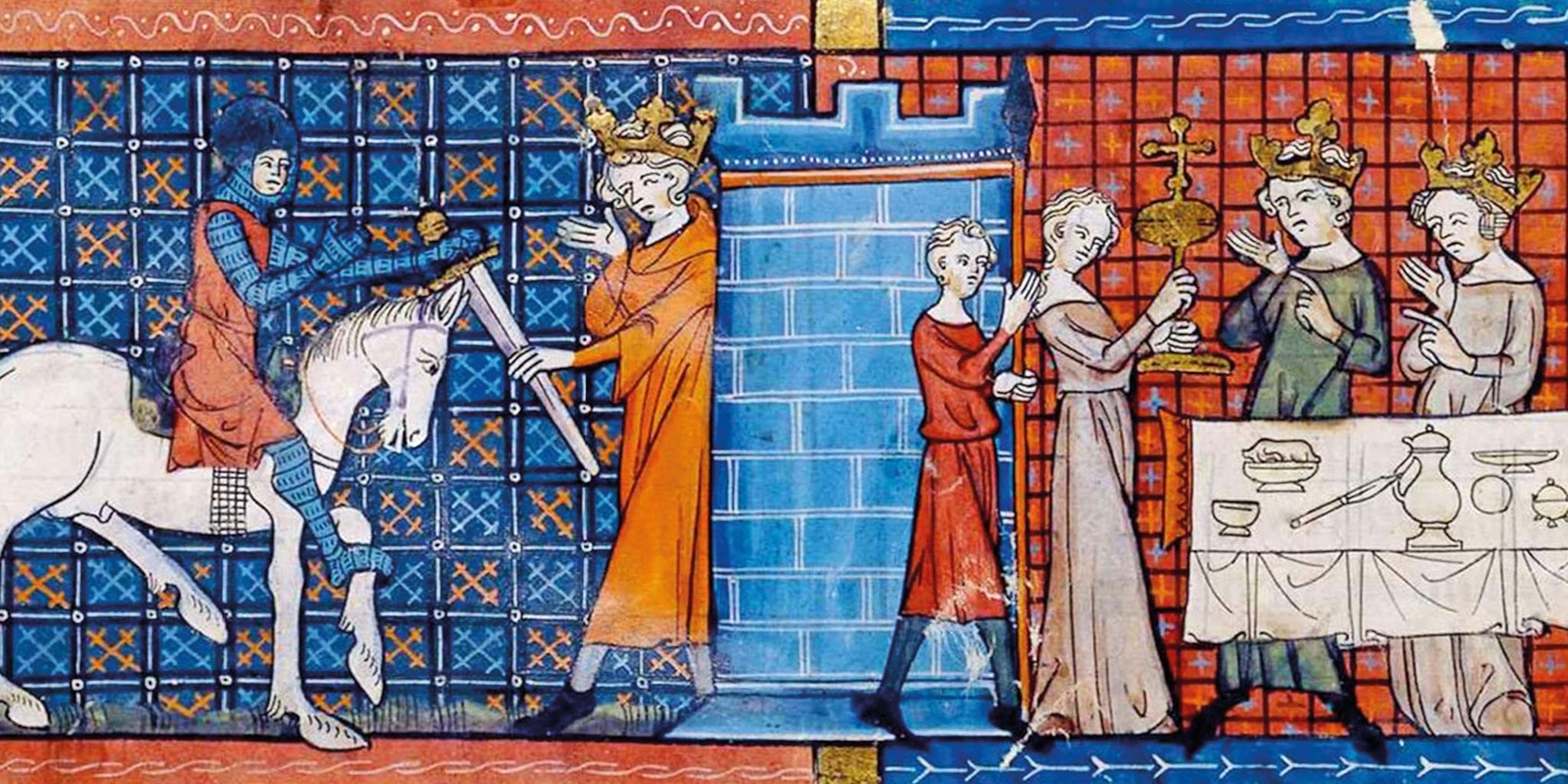

The vessel becomes even more central in the late 12th century. Marie de France, a French poet at the English court, wrote poems about Arthur and the Grail. Chrétien de Troyes penned five Arthurian romances, including Perceval, the Story of the Grail. In this work, in which Perceval the knight is tested in various ways, the Grail is depicted as a mysterious serving dish. It is neither holy nor yet the object of a quest, but it does have supernatural value and healing power. Perceval plays a main role in German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. Written around 1300, this romance recounts how the knight is eventually crowned Grail King after many adventures.

By 1220 an array of Arthurian conventions had been established in the Old French poems modern scholars collectively refer to as the Lancelot-Grail cycle. The educated readership came to know the dramatic settings of Arthur’s world: Avalon, the enchanted island; Camelot, home of King Arthur and his knights; and Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, where Arthur was said to have been conceived. This rich world formed the backdrop for the many adventures of the knights of the Round Table.

(Some islands, like King Arthur’s Avalon, were pure legend.)

The quest for the Grail was also by then one of the principal story lines in the Arthurian tradition. Others include the troubled love triangle between Arthur; his wife, Guinevere; and the knight Lancelot. These story lines came to inform one another. Lancelot’s erotic entanglements, for example, complicate matters as to whether he was sufficiently worthy to receive the Grail.

Another celebrated object of the Arthurian romance was the Round Table. The scene of Arthur and his knights gathered around this table symbolically recalls the Last Supper. In a deeply Christian age, such powerful imagery infused Arthurian texts and Grail legends with a sense of holy purpose, as well as with redemption and healing.

A seat at the Round Table

Keepers of the Grail

The real and the fabulous are seamlessly blended in the Arthurian stories about the Grail. The tales inhabit a time and place that seem factual yet cannot be pinned down, allowing them to be identified with people and places across Europe. Semi-historical characters who live at different moments in history, such as Joseph of Arimathea (first-century Palestine) and Arthur (sixth-century Britain) are mixed with fantastic characters such as the wizard Merlin and the enchantress known as the Lady of the Lake.

(Who was Merlin the Great, really? Here’s the history.)

In 1200 the poet Robert de Boron worked the Arthurian legends into a Christian frame-work by introducing the figure of Joseph of Arimathea. In the Gospels, Joseph arranges for Jesus’ burial following the Crucifixion. According to de Boron, he secretly keeps the Grail from the Last Supper and uses it to collect the blood spilled when Jesus’ body was pierced on the cross. Joseph’s family later traveled to England with the precious object, explaining how the Grail came to Britain.

Another key figure is the mysterious Fisher King. He first appears in Chrétien de Troyes’s version of the Perceval tale in the late 1100s and likely has deep roots in much older Welsh literature. Iterations of the Fisher King appear in later Arthurian texts in which he plays various roles. Despite some differences, there are recurring characteristics: He is a ruler, he is wounded or maimed in some way (sometimes in the groin or thighs), and he awaits a figure who can heal or redeem him. In some works he is the keeper and protector of the Grail. From the first Arthurian texts of the 12th and 13th centuries to Le Morte d’Arthur, written in the 15th century, the Grail stories caught the spirit of the age. In part this was because of their dense spiritual symbolism, but they also hinged on an exciting plot device still used by cinema and fiction today: the hero’s journey.

Tellings and re-tellings

After 1210, when the stories in the Lancelot-Grail cycle were written, a common theme of the sacred quest began to take shape. While the chalice itself was understood to be a physical object, its search had a profoundly spiritual underpinning. Knights in pursuit of the Grail represented a desire for individual improvement, the seeking of an unattainable end as part of the spiritual path toward perfection.

(These medieval knights were the 'superheroes' of their time.)

Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur was produced toward the end of the Arthurian heyday in the 15th century. The text was built on a tradition in which only one knight would be able to resist all the temptations thrown in his path, as Jesus had done when he resisted the devil.

First champion of the Grail

In Malory’s telling, the quest begins after Galahad pulls a sword from a magic stone in Arthur’s court, proving he is a knight of exceptional virtue. Together with Gawain, Percival, Bors, and Lancelot (his father), Galahad goes searching for the Grail. After many adventures, the knights discover that their various moral failings (in the case of Lancelot, his impure thoughts for Guinevere) will keep them from the Grail—all except for Galahad, who reaches the Grail Castle, heals the Maimed King (the Fisher King), and finally sees the holy vessel.

On his return, Galahad is imprisoned in a “dark hole” by an evil king, but the Grail saves him by producing food and drink. On arriving home with the Grail, Galahad is crowned king. The full mysteries of the Grail are then revealed to him by the spirit of Joseph of Arimathea:

... the Lord has sent me hither to bear you fellowship. I was chosen because you resemble me in two things: You have witnessed the marvel of the Holy Grail, and you are a virgin—as I was, and am.

As the Arthurian tradition shows, however, the Grail does not have to physically exist to fire the imagination. One variant of the lost Grail story has Mary Magdalene bringing the cup to southern France. This account underpins the 1982 book by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, a best seller regarded by historians as pseudohistory. Some of the book’s central ideas, in turn, inspired Dan Brown’s 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code. Quest stories about the mysteries of the Grail can become literary blockbusters in the 21st century as easily as they did in the 13th.

Tales of the Grail’s power—and the lengths to which people will go to acquire it—are often as ornate as the purported object itself, usually of high-value craftsmanship. Ironically, Christ’s humility would suggest the opposite. “That’s the cup of a carpenter,” Indiana Jones states in the 1989 movie about a 20th-century quest for the Grail, set against the backdrop of World War II. He wisely selects the most modest-looking chalice from the dazzling selection. The fictional archaeologist is on firm theological ground. As the fourth-century Early Church Father John Chrysostom wrote: “The chalice was not of gold in which Christ gave His blood to His disciples to drink, and yet everything there was precious and truly fit to inspire awe.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam