Five children from China born with malformed ears have had them regrown using cells from their own bodies.

Using a groundbreaking process to grow body parts from cells in a laboratory, researchers in China gave the children ears to replace their own, underdeveloped ears. They each had a condition called microtia, which causes their ears to be extremely small and misshapen.

The researchers began by taking a computed tomography imaging scan of each patient's normal ear. That image was then reversed and 3-D printed. A mold of the printed ear was filled with a biodegradable substance that would dissolve in the human body. This shape acted as a scaffolding; cartilage cells from the patient were added to it which could then grow on their own. As the cartilage cells divided, the scaffolding, which subsequently dissolved, forced them into the shape of an ear.

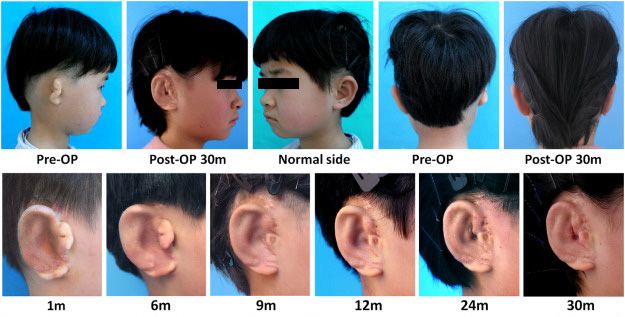

That false ear was implanted under each patient's skin, which had been expanded to accommodate the shape. The result is an ear-shaped organ, made in the lab and grafted onto a patient, ready to wear it out in the world.

So far, all signs point to the procedures being a success.The first patient received her ear two and a half years ago and hasn't reported any problems. Neither have the other four children who received their new ear more recently. The results were recently published in a study in the journal EBioMedicine.

The History of Growing Ears

This treatment is directly derived from a more famous experiment growing ears on the backs of mice.

Just over 20 years ago, researchers in Boston set out to create human body parts from scratch. They, too, began with ears. They created several ear-shaped scaffoldings, seeded them with cow cartilage cells, and implanted them on the backs of mice.

Joseph Vacanti, a doctor at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, was among the team that developed this ear-growing technique. A photograph of one of the mice became famous as an icon of scientific advancement, and became known as The Vacanti Mouse.

Although the mouse inspired some fears of the power of science, the research has helped humans. A senior author on the new study was also a major contributor to the research that led to the so-called earmouse, Vacanti noted to Newsweek by email. The main difference between the research in mice and the human patients is that the scientists created the ear cartilage shape with cells from the patients themselves, so the human patients' bodies won't reject the new part.

It's important to continue to monitor the patients as they grow to see how their ear responds. However, this procedure is considered a success so far.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kristin is a science journalist in New York who has lived in DC, Boston, LA, and the SF Bay Area. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.