“Scotty, I need warp speed in three minutes or we’re all dead,” Captain James T. Kirk firmly tells his lieutenant commander in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982).

The USS Enterprise then catapults away at warp speed, leaving behind streaks of light from the surrounding stars, because warp speed is faster than the speed of light. Throughout Star Trek and many other works of science fiction, warp-speed travel is essential for voyaging where no human has ever gone before.

Unfortunately, warp speed doesn’t exist in the real world—not even close. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t possible.

“We can say it’s probably unlikely,” Miguel Alcubierre, a professor at the Institute of Nuclear Sciences at the National University of Mexico, tells Popular Mechanics. But “at the moment, we can’t say it’s not possible.”

Alcubierre is a longtime sci-fi fan and an accomplished astrophysicist. In the early 90s, while studying gravitational physics for his doctorate degree, an episode of Star Trek inspired him to look into the theoretical possibility of warp speed.

At that time, the show “never actually explained how [warp speed] works, it was just a name for whatever they do to travel faster than light,” he says. So Alcubierre came up with a way to modify the geometry of space “that in principle would allow us to travel faster than light,” and at the same time, doesn’t violate the laws of physics.

His solution is based on the fact that the universe is expanding—something scientists have known for about 100 years. Alcubierre figured that if all of spacetime itself can expand, then it should also be able to expand in a small, regional space. And if it can expand, then it must be able to contract.

The Limits of Warp Bubbles

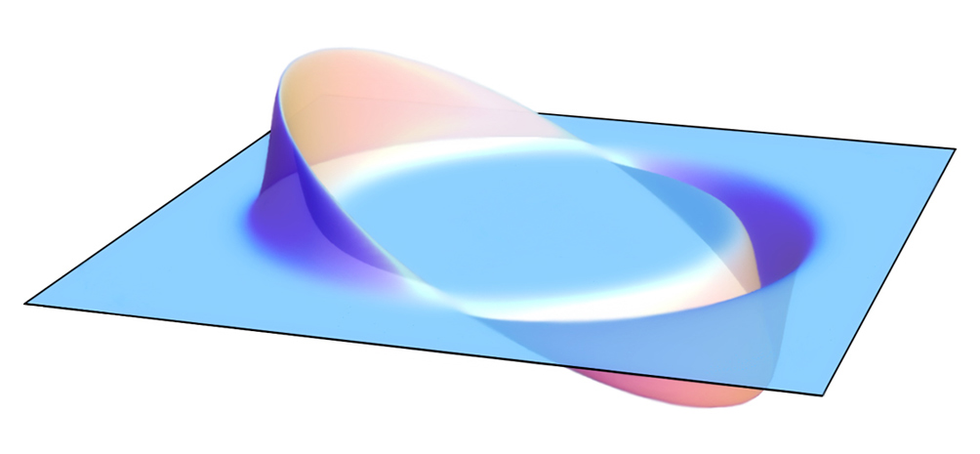

“The basic idea is just to create an expansion of space behind, say, a spaceship, or whatever object you want to move, and an opposite contraction of space in front of you,” he explains. In other words, a warp bubble.

Alcubierre explained his theory in a famous 1994 paper that describes what’s now called the Alcubierre drive. “I always just call it warp drive,” he says.

The easiest way to understand the warp bubble is to picture spacetime as a trampoline, explains Erin Macdonald, an astrophysicist and the current science advisor for the Star Trek franchise. “Put a bowling ball on that trampoline, and it’s going to dip spacetime down, and that’s like what the mass of a sun or a planet or anything like those do to spacetime,” she tells Popular Mechanics.

When items with significant mass need to move, the fabric of spacetime limits their speed. The lighter something is, the easier it can move across the fabric. “Then eventually, if you have no mass, you’re not tipping [the fabric] down at all. And you just coast in a straight line at this fixed speed, which is the speed of light, because light doesn’t have any mass.”

That’s currently the limit to how fast anything can travel, because as soon as you introduce mass—and something like a spaceship definitely has mass—it physically can’t travel faster than a certain speed because it’s bending spacetime. “But nothing says that spacetime itself can’t go faster than the speed of light,” Macdonald says, “and that’s the warp bubble.”

A spaceship traveling at warp speed wouldn’t be firing its engines to travel that fast; it’s just being carried by a spacetime bubble. Then if you want to exponentially increase your speed, you build another bubble around that bubble, which in the world of Star Trek is referred to as warp factor two, and then warp factor three, Macdonald says.

Spacetime as we know it is finite, and as such, there is a limit to the number of warp bubbles, or level of warp speed one could theoretically reach. In some shows, this is arbitrarily called warp factor 10, which is when all of spacetime is wrapped around the spaceship. At that point, “you’ve broken all the laws of infinity and you experience all time at all moments,” Macdonald says. “And in the classic Voyager episode of Star Trek, you evolve into lizard people.”

Harnessing Negative Energy

The main reason warp speed probably isn’t possible is because it would require a currently impossible amount of energy. Einstein proved that E=MC², which means energy and mass are interchangeable. That means in order to travel faster than the speed of light, the object would need to have negative mass and therefore, negative energy—two things that, as far as we know, don’t exist.

✅ Know Your Terms: Negative energy is a concept allowed in quantum theory that describes an energy state of less than zero, and it would necessitate negative mass. Since positive masses attract one another, gravity could become a repulsive force in the case of negative masses.

And even if we could figure out a way to create negative mass or negative energy, we would need enormous amounts of it to move a spaceship. “To move an ordinary airplane at just the speed of light, not even faster, you will need to transform 60 times the mass of the planet Jupiter into negative energy,” explains Alcubierre. That’s not exactly practical.

Even then, it would still take us four years to reach the closest star, Proxima Centauri. However, if warp speed were possible, it would suddenly make all of the stars and planets in the universe a lot more accessible, which is exciting to think about.

“I just love the fact that it is theoretically possible,” says Macdonald. “The math does work. It’s not one of these things that physics just straight up says that can never ever happen.”

Kimberly is a freelance science writer with a degree in marine biology from Texas A&M University, a master's degree in biology from Southeastern Louisiana University and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work has been published by NBC, Science, Live Science, Space.com and many others. Her favorite stories are about health, animals and obscurities.