Beauty

What "The Last Unicorn" Means to Us Today

A metaphor for our search for belonging.

Posted March 21, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

“I am a little afraid to go home. I have been mortal, and some part of me is mortal yet. I am no longer like the others, for no unicorn was ever born who could regret, but I now I do. I regret.” —animated film "The Last Unicorn" (1982)

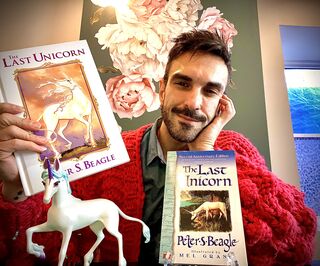

I’m sitting in my office, considering the magnitude of events that led us here. We have all been on, and continue to tread, uncharted territory in a world forever changed. We’re searching for something familiar. Something we know. We search for belonging. The world has changed, the “before times” fading into the backdrop of a new world. I look over at my desk, and consider a statue from The Last Unicorn, an 80’s cult classic film about a unicorn, the last of its kind, on a journey to find out what quite happened to the others—a dangerous and life-altering journey. I’m stuck on the image of a unicorn, facing a fiery red bull, standing between herself and her kind, and the need to find belonging again and to restore the world to what it was. It's a dynamic battle against a tangible foe, and also a psychological one, in that she is now different than the other unicorns. This journey altered her world.

A pause.

I love this film, and use it clinically at times to help clients make sense of a world that doesn’t see them. I’m a psychotherapist, but more important to this narrative, this is my practice: I am a LatinX, Gender Queer person living with a disability. I’m also a trauma survivor. I am also a geek therapist and toy analyst. In my seat, across from my clients, they rarely know elements of my private life, but I see them — many of them — in their journey and recognize it in myself. The countertransference is tangible. We are searching, together, like the unicorn, for others like us.

I’m dating myself, as the film is a cult classic that most Gen-Xers will recall gave them a fright. The film is quite adult, and yet, this year, marking its 40th anniversary, author Peter S. Beagle’s story is more relevant than ever in a pandemic world. You see, the unicorn searches, and searches, and along the way experiences things she, as a unicorn, would normally not have exposure to: death, mortality, human love and loss, and regret. All in the name of belonging.

Human behavior is often characterized by a need to belong. It informs our sense of self, be it in the attachment we form with others (relational sense of self) or the social groups we see ourselves in — our shared community (the collective self). We are often stuck between understanding our human experience in the “I” versus “We” (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). I work primarily with LGBTQIAA+ people, across the lifespan, often finding my specialization in the area of trauma-informed care. But what I often see is not biopsychosocial in our traditional sense of understanding psychology, it is the journey — the experiences of Queer people trying to understand themselves in relation to a world that doesn’t see them. I too, although across the seat as a therapist, commune in this sense of longing to belong. I often feel like a unicorn — and the last — as I sit with clinical knowledge as a clinician, but as a Queer person, whose childhood is marked by a journey that was both magical in my difference from others and traumatic, in battling the unwavering hardship of being mocked, shunned, and reminded that I was different. I recall watching The Last Unicorn as a child, and feeling seen. The adult-oriented script of the film somehow made sense to me. I continue to watch it, and read the original novel, and find something new about myself, psychology, and people, each time. The film always stands out as uncompromising in its approach to the parallel of the human experience of belonging, complete with loneliness, happiness, curiosity, danger; all of the complex experiences central to our biopsychosocial development.

You see, the film is deeply rooted in human experiences and psyche in that it illustrates the contradictions that make human awareness unique. The story, as film critics delight in denouncing, does not have a happy ending, but a neutral one that is both fulfilling and beautiful. And it is in the bleakness of the story that we find beauty. The Last Unicorn is no traditional fairytale; it is a harrowing depiction of real life. I think that is what I love most about it. The unicorn is a symbol of beauty marked by the human world she encounters, learning about that notion that pain leads to growth, that humans are not immortal as she is, that life is framed by our experiences with the world around us, and yet, we as humans come and go, there is no end, only other journeys to observe.

As the film states, “There are no happy endings, because nothing ends.”

This may feel deeply sad, as we celebrate National Diversity Month in April 2022, reliving the world in our thoughts since the changes that came in 2020, both in the human experience and in history. We, like the unicorn, sought out a journey these past few years, to find others like us, and now here we are, as very different people, across the world, but the collective self, the “We,” sees there is no ending per se, because things may change but the world moves forward. I consider this, because I believe that we must continue to celebrate our awareness of difference, the beauty in our contradictions in wanting stability in a world where nothing is ever stable. That is what makes us human, and I think about all my experiences, and my clients' experiences, and our collective research on psychology and social science, and here we are…a we, a generation of people raising children and supporting each other and living as best we can in a world that is illusive. It takes immense psychological resiliency to be where we are today.

Actor Alan Arkin, who plays the character Schmendrick in The Last Unicorn, has a line in the film that I keep on a sticky note at my desk: “It's a very rare person who is taken for what he truly is.” I hope we all, as people, may take a step back, not just in National Diversity Month, but always, to try to see people for who they are, and meet them where they are. It may help our collective “we” to feel less polarized and alone. I hope that we can learn from the unicorn, 40 years later, that the journey is worth it, and we will find others like us. But here’s the duality, yet again: They aren’t the same, because it is our experiences with the world, individually, that set us apart from one another. So even in our most relational experiences, where we find intersections that we share with others, we are still unique and diverse. And I love that. It means there’s only one of you, one of me, and it makes me at times, feel like a unicorn—mystical, curious, and illusive. Maybe we are all unicorns, searching in a world where we think we know exactly who we are, only to travel it, and come out changed. And be able to see the difference from where we began our journey to who and what we have become.

At one crucial point in the film, the unicorn becomes human for a time and experiences pain and loss, and is told by the magician accompanying her on her journey, “Don't cry. If you have become human enough to cry, then all the magic in the world cannot change you back.” I think about that, because she does change back into a unicorn, yet, she is different from the others: She has lived in a mortal body for a time and finds out our time is marked by not only the clock, the date, the years, but in our ability to feel, to love, to lose, and that is what makes a life.

I think back to that small Queer child in the early 80’s watching that film, and want to tell them, You’ll find others like you, but no one can be you. And in that, there is magic, but to grow, you will need to be able to be unique, while also finding community. It takes others to grow.

Or, as I often say, “It takes a village to raise a unicorn." Let’s all be each other’s village. There’s a world of unicorns out there, and hopefully, they will never have to worry that they are the last.

Peter Andrew Danzig (they/them), LSW, MSS, CTP is a therapist, toy analyst, DEI professional, and author. Their book, Don’t Toy with Me: A Geeks journey to Acceptance, Calm, and Expression, is due out in 2023 by Leyline Publishing.

References

Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this" We"? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83.