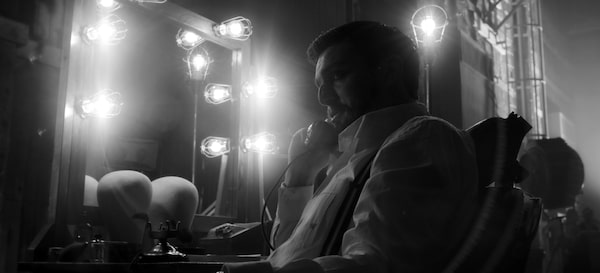

Gary Oldman as Herman Mankiewicz, Arliss Howard as Louis B. Mayer and Tom Pelphrey as Joe Mankiewicz in David Fincher's Mank.Netflix

- Mank

- Directed by David Fincher

- Written by Jack Fincher

- Starring Gary Oldman, Amanda Seyfried and Tom Burke

- Classification R; 131 minutes

The very simplest summary of David Fincher’s Mank is that it is about the battle for creative credit over Citizen Kane. In one corner is screenwriter and infamous wit Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), forever bloated and bloviating, fighting to leave his mark on the world. In the other is brash director Orson Welles (Tom Burke), at the peak of his powers and adamant that dear ol’ Mank, as he’s known to everyone in the small town that is Hollywood, remains on the margins of history.

So that’s the easy synopsis. But nothing about Fincher’s film is easy. Indeed, for one film about how internal conflict almost tore another film apart, Mank is uneasily built on its very own base of destabilizing, contradictory anxieties. It is a credit-battle away from crumbling completely.

That won’t happen, though. Mostly because the writer of Mank is Jack Fincher, David’s journalist father. But also because Jack is dead, and has been since 2003, long before the cameras started rolling on Mank. Which, now that it’s out there in the world, makes for one of the strangest and hall-of-mirrors-y father-son collaborations ever.

Oldman brings an easy charm and quick tongue to the perpetually soused Mankiewicz.Netflix

Consider the following: By arguing that Citizen Kane is more the product of Mankiewicz than Welles, Mank’s screenplay effectively distances its director from questions of control and intention (and revives the theory of a legendary and long-discredited Pauline Kael New Yorker essay). Yet in dusting off and revising Jack’s screenplay (with help from an uncredited Eric Roth), Fincher acknowledges that any act of cinema is collaborative at best and inherently bound by the director’s process and vision. But that’s not all.

By making a 2020 movie (for Netflix!) about a 1940s movie that also looks and sounds like it was its own 1940s movie – Fincher shoots in black and white, adds digital “cigarette burns” to denote non-existent reel changes and limits composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross to era-appropriate instruments – Mank appropriates the notion of authenticity while simultaneously toying with it. By casting the dashing Burke, who approximates Welles’s deep baritone and slick presence like no one else, Fincher aims for spot-on verisimilitude. But by asking the then-61-year-old Oldman to play Mankiewicz (who is shown from ages 32 to 43 over the course of the film), the director offers an eager middle finger to the notion of credibility. And by dangling a delicious inside-Hollywood story but delivering a treatise on socialism, Mank executes a bait-and-switch for the ages.

Mank is, overwhelmingly, so very interesting. But it is also something of a half-masterpiece mess: thematically scattered, awkwardly paced, overlong and curiously uninterested in the inner life of its title character. Your mileage for Fincher’s specific mode of film-theory-in-motion may vary, though. Because while untangling Mank is almost as much fun as it must have been for audiences to decode Citizen Kane back in the day, there is a difference between solving Fincher’s cold, hard puzzle and Welles’s shiny, beautiful enigma.

Amanda Seyfried has never been better than she is here as Marion Davies.Netflix

It is easy to tell what works. Working with his Mindhunter cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, Fincher’s camera constantly aims to amuse. So many of the film’s shots are dryly amusing. The first time that Mankiewicz meets actor and William Randolph Hearst mistress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), whom he would later betray by using her as the basis for Susan Alexander Kane, she’s being burned at the stake as part of a film shoot. Every time we encounter golden-boy producer Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley), he’s situated directly next to MGM honcho Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard), denoting his right-hand-man status. And then there are the many visual allusions to Citizen Kane itself, all deep-focus compositions and moments of light-trickling beauty.

The performances are aces, too. Despite being far too old for the role, Oldman brings an easy charm and quick tongue to the perpetually soused Mankiewicz, who can endear even when he’s vomiting up his dinner (“It’s all right, the white wine came up with the fish”). Seyfried has never been better, or never been given the opportunity, as the too-smart-for-the-room Davies. Despite only fleeting screen time – and much of it viewed from the perspective of a barely cognizant Mankiewicz – Burke is impressively intimidating. And the many actors who Fincher has populate the rest of his Hollywood tale – Howard’s feisty Mayer, Charles Dance as Hearst, Joseph Cross’s budding screenwriter Charles Lederer – are delightful.

Yet despite the current film-circle chatter and Netflix-backed marketing, Mank isn’t a love letter to the Golden Age of Hollywood. It’s more a manifesto, written with a poison pen. The Citizen Kane credit battle only takes up 15 minutes of the film’s run-time, and then only at the very end (for a more detailed film about the fight, see HBO’s 1999 film RKO 281). Mostly, the Finchers are not interested in how movies get made but why, and use Mankiewicz’s position in the studio system as a way to expose the politics that greased the wheels of the dream factory.

Tom Burke is impressively intimidating as Orson Welles.Netflix

The name “Orson Welles” is uttered far fewer times, for instance, than that of Upton Sinclair, the socialist writer who lost California’s 1934 gubernatorial election to Republican Frank Merriam, thanks to the significant help of Hearst and Mayer’s pioneering work in the art of Hollywood-funded fake news. (It’s telling that no actor was cast to play Sinclair; in Hollywood, an idea is more dangerous than a single man.)

Mankiewicz, a writer whose own ideologies were infamously tricky to parse, ends his journey here half-awakened to his own role in the industry, half-corrupted by the corrosiveness of greed and power.

This journey isn’t unwelcome, exactly, just not sticky enough to truly captivate and enthrall. Fincher understands Mank’s world so damn well – the director certainly relates to Welles’s sentiment that Hollywood is “the biggest electric train set any boy ever had” – just not his title character’s place and purpose within it.

Aside from Citizen Kane, Mankiewicz’s most famous bit of writing might be a telegram he sent to writer Ben Hecht in 1925 (it’s repurposed in Mank as a letter to younger brother Joseph Mankiewicz): “Will you accept three hundred per week to work for Paramount Pictures. All expenses paid. The three hundred is peanuts. Millions are to be grabbed out here, and your only competition is idiots. Don’t let this get around.”

Fincher is, obviously, no idiot. But Mank feels closer to a fool’s errand than a work of staggering genius. Don’t let this get around to Netflix, though.

Mank opened in select Canadian theatres Nov. 20, and is available to stream on Netflix starting Dec. 4

Plan your screen time with the weekly What to Watch newsletter. Sign up today.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz