The director Robert Altman used to tell Peter Gallagher, the suave star of his 1992 movie The Player: “Gallagher, you’re so good-looking it makes me sick.” To hear Gallagher impersonating the gruff auteur, it was not quite a compliment. But he was used to that.

During a heated rehearsal for The Real Thing, Gallagher’s breakout role on Broadway at the age of 29, another director, Mike Nichols, admitted to not being able to stand the sight of him. “And we were close!” says Gallagher cheerfully, speaking over Zoom from his home in Los Angeles. He responded by growing an “awful white goatee” until Nichols pleaded for him to shave.

Critiques of Gallagher’s performance often linger on his looks. They seem integral to the cocksure ne’er-do-wells he plays: from a vengeful spouse in Altman’s Short Cuts, to a lawyer sleeping with his wife’s sister in Sex, Lies and Videotape, to the braggadocious “real estate king” in American Beauty. Altman said he cast Gallagher as a shortcut to character, just his face communicating “handsome, vain, sleazy”.

Even at 64, Gallagher continues to play bad guys: an absent father in the sitcom New Girl, a three-time divorcee and white-collar criminal in Netflix’s Grace and Frankie. “It has a lot to do with how I look,” he agrees. “When I was younger, I had the kind of face that if I saw me walking down the street, I’d say: ‘What an asshole! Look at that rich kid who’s had everything handed to him! Fuck him!’”

Yet Gallagher has little in common with his privileged parts. From working-class Irish-Catholic stock, he carved out a 40-year career in show business by “showing up”, he says. “The only thing I know is you’ve got to be willing to work harder than everybody else.” Even now, quarantining at home, Gallagher is practising singing daily, so as to “not completely go to seed”.

The character he seems most like is Sandy Cohen, the statesmanly patriarch of the 00s teen-dramedy The OC, one of television’s greatest-ever dads. “After Bill Cosby fell a few spots …” he jokes drily. As a father, to film-maker James and musician Kathryn, Gallagher says: “I try to be Sandy Cohen. I never, ever wanted my kids to see me angry, because I know that anger just stops a kid. It chokes everything off.”

Gallagher’s own childhood was characterised by that emotional instability. “The impression was we were always sort of living on the edge.” He was born in New York City in 1955, the unplanned youngest of three. He was close to his mother, a bacteriologist, but for much of his childhood she suffered from social anxiety and depression, which he connects to her parents’ experience of emigrating to the US from Ireland. “She would be unable to get out of bed, and I had to take care of her.”

Gallagher’s parents, both of whom are dead, fought constantly. He remembers, at age six, seeing the family’s brand-new television sailing through the air. “I used to pray for them to get divorced, it was just so noisy sometimes.”

Later, as an adult, he saw the love between them, and “that there was grace to be maybe had, if you stayed the course”. That has informed his own marriage, to Paula Harwood, a former producer turned interior designer, whom he met in his first year at Tufts University in Massachusetts. This month they mark their 37th wedding anniversary, which is, says Gallagher, “embarrassing for Hollywood”.

But his relationship with his father – a second world war veteran and advertising executive – casts a long shadow. Gallagher describes a distant, dismissive figure. “I would try my whole life to reach him, just to get him to respond to me. ‘Dad, what were you in the war?’ ‘A general. Now go clean the gutters.’ ‘Dad, what are taxes?’ ‘You’ll figure it out.’”

Young Gallagher took his father’s indifference as a personal failing. In his career – he says, in that cogent way that comes with therapy – he sought out surrogates such as Nichols, Altman and his co-stars Jack Lemmon and Peter O’Toole. Lemmon gave Gallagher a set of golf clubs. O’Toole took him to a football game.

On stage, following a script, Gallagher felt liberated, finally confident he “wasn’t doing anything wrong”. In fact, he was getting enough right to land the part of Danny Zuko in Grease on Broadway, from an open audition in 1978. Yet he was not immune from the fickleness of show business. He notes the irony of “the best creative experience I ever had” – 1984’s The Real Thing, alongside Glenn Close and Jeremy Irons – precipitating his quarter-life crisis of confidence. Despite all his promise, opportunities dried up. Now Gallagher blames his agent; then it coalesced with his “self-loathing, lack of confidence” and childhood trauma. “I started to question every morsel of my being until I couldn’t really function.”

Even in his depression, Gallagher recognised he was at a “transition point … I could keep banging my head against the wall and have a tragic outcome – or pay attention to what was going on inside.” He quit the play and started over, with therapy and acting classes. “It was like a key into a lock.”

Focusing on the craft allowed Gallagher to distance himself from the outcome – for better and worse. What he identifies as his career low, the 1992 Broadway revival of Guys and Dolls, was a critical and commercial hit. But Gallagher felt boxed in by the director, prevented from giving his best; that “rough treatment” led him to avoid musicals for 25 years.

“When something works in show business, it’s a miracle,” says Gallagher – so he has little time for big egos making it harder. Seeing someone get fired on a film set “just for a power thing” made a lasting impression. “One of the most toxic things in the world is success. I’ve seen people think they have all the answers, like: ‘If I’ve succeeded at this, then there’s nothing I can’t succeed at!’ You want to say: ‘Dude – you’re a member of the effin’ lucky club.’”

Given his consistent career, it could seem surprising that Gallagher never made it as a leading man. In 1993 the New York Times noted how “lady luck” was resistant to his “lubricious charm”. Gallagher puts it down to his inability with self-promotion. For years he wanted to prove that “it’s not who you know, it’s how good you are” – but, he laughs: “That’s fucking stupid, because [who you know] means a lot. I just don’t have the confidence socially.”

Besides, he says: “I think the whole idea of stardom is kind of baloney; I never really bought into it. I wouldn’t have had the skills, the way of thinking … I’ve seen the people who have achieved it, and what they’ve done to get there.”

There is more freedom to being a character actor, he says; more scope to surprise. The benefit to playing bad guys is that the parts were often underwritten. “They just wanted him to be an asshole … so it gave me a little elbow room,” says Gallagher. In the 1995 romcom While You Were Sleeping, he resisted the writers’ attempt to zhoosh up his character by making him an “awful person”, instead of just poorly suited to Sandra Bullock. “Why burden the audience with someone to hate? There’s just more opportunity in playing the character truthfully.”

He served as a similar check on The OC. At just 26, the showrunner, Josh Schwartz, was open to his input on “the parent stuff”, says Gallagher – so each week he and Harwood would go through the script: “Aw, jeez, if I said that, they should just send me to social services.” “Mischa [Barton, who played troubled young Marissa Cooper] spends the night with my business partner, and I’m supposed to say: ‘That’s cool’? No way!”

For all the writers’ occasional “capriciousness”, Gallagher says The OC was successful because of “the organism of the ensemble” – and the timing. Post 9/11 the US had “run with the wrong ball”, closing borders and embracing xenophobia, “the most cowardly, un-American thing”. Sandy Cohen was a corrective: a principled public defender, a New York Jew married to a gentile Californian, “not afraid to welcome others into his home. I thought that was the perfect story to be telling.”

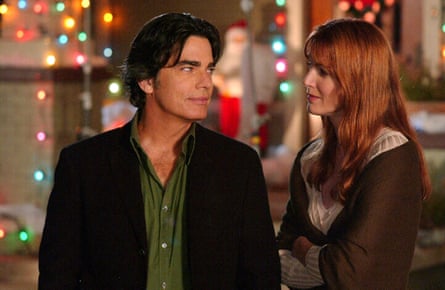

Gallagher sees parallels with his latest project, Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist, which just concluded its first season on NBC (E4 in the UK). In the whimsical musical dramedy, Zoey hears others’ private thoughts as songs – highlighting, for Gallagher, the importance of a sympathetic ear “in an era when we’ve been intentionally divided”.

The Trump presidency has special significance for born-and-bred New Yorkers, he says sombrely. “We knew his father was a white supremacist,” he says, but they didn’t take Donald seriously until his attacks on the Central Park Five, a group of black teenagers who were wrongly convicted of the 1989 rape of a woman. “We realised he was no longer funny; there was a darkness, and a willingness to do harm.”

Still, it was a “no-brainer” to look to Trump for Buddy Kane, Gallagher’s ludicrous character in American Beauty: “I thought, who has the hugest opinion of themselves in real estate?” Gallagher was made heavier and older, and approximated the “pouffey thing going on” with an old wig of Cary Grant’s. “So when I was in bed with Annette Bening, Cary Grant was on top of her.”

Twenty years on, it is “heartbreaking”, says Gallagher, to see the country “bamboozled by this con man … It really feels like they left the back door of the Capitol open.” He mimes a bandit, egging others on. “Take anything you can and get the hell out before they catch on! You want the parks?”

And amid coronavirus, the stakes have never been higher. Gallagher winces: “It’s a little painful, having been raised by a bacteriologist mother, to hear someone blatantly disregarding science.” His mother had helped to develop the Romansky formula during the second world war, revolutionising the administration of penicillin. She died in 2004 after a 20-year struggle with Alzheimer’s disease.

The experience informed his role in Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist; he plays Zoey’s father, who is paralysed by progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a somewhat similar brain disease. “What gave me some relief was that PSP doesn’t always find the same expression in people,” says Gallagher. The series creator, Austin Winsberg, whose father died of PSP, was also a check. “I knew that if I was screwing it up, he’d go: ‘No!’ And if he was leaving because he had to cry, I thought: ‘I’m in the ballpark.’”

Gallagher has been gratified by praise from people with experience of PSP, or of caring for a parent – but some criticised his casting, as an able-bodied actor. What is his view: that disabled parts should go to disabled actors? That there is a limit to the experience that can be portrayed by acting? Gallagher flips the question: “I would say, people with disabilities shouldn’t be automatically excluded from playing any role.” He notes that one episode features deaf actors and musical numbers in sign language. And “hard and fast rules about who should do what” do not recognise the hurdles a project has to clear in order to get made, he says, with mounting (and somewhat surprising) impatience.

The answer, as he sees it, is more, and more diverse stories – and by that measure progress is fast. He points to Grace and Frankie, in which he plays Jane Fonda’s love interest. “What an extraordinarily disruptive notion: people older than 25 have life experience that deserves investigation and sharing!” he says with good-natured sarcasm. “And, my God – there are people 25 and under that want to watch!”

It is the chance to be part of those stories that have “a place in the world” that keeps Gallagher singing his scales in quarantine and, he believes, will see show business through the challenge of coronavirus. “Broadway was supposed to be over with 9/11; it turned out to be exactly what the world needed. And what are people doing in quarantine? They’re watching a lot of Netflix. Because these stories are important.”

And even the bad guys have a part. Days after 9/11, Gallagher was asked to go to Ground Zero to boost the morale of emergency workers who had missed out on visits from the president and the Yankees. “The fires were still burning, the smell of death …” Gallagher’s last big picture had been American Beauty. “I’m thinking: ‘What have I done with my life? I’ve got to change jobs, do something that counts.” And all of a sudden, one of the firefighters …” Gallagher erupts in a New-Yoik holler. “‘LOOK WHO’S HERE! ‘FUCK ME, YOUR MAJESTY’, IT’S THE KING!’”

Buddy Kane was an asshole. But they were still glad to see him.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion