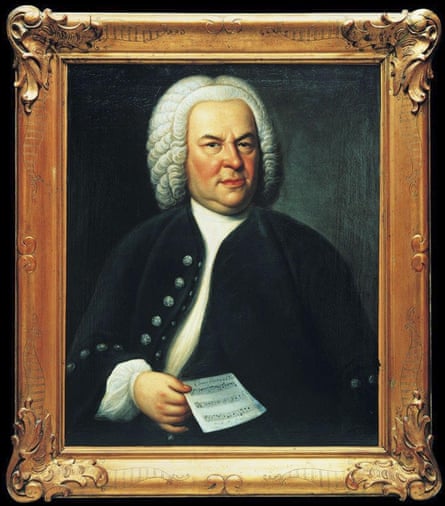

As the white shroud was whipped away, it was as if the great composer himself had made an entrance on stage. Gasps and applause greeted the unveiling of the portrait of a man in a white wig, with a stern expression on his plump face, and a half-smile of approval on his fleshy lips as he proffered a music score to his audience.

The boys of the St Thomas choir strained to see the picture of the man who had been their cantor for 27 years, as the 12th century St Nicholas church played host to the emotional homecoming of the best contemporary likeness of Johann Sebastian Bach. Before Friday, it had not been on public display for 267 years.

While hundreds of dignitaries, musicians and Bach experts from around the world gathered in the church – famous as the setting of the peaceful 1989 revolt against the communist regime of East Germany – many more were in the nearby market square to watch live on a huge screen the unveiling of the oil painting. The city’s mayor, Burkhard Jung, called its return a “blessing for Leipzig”.

The Leipziger Zeitung said it reinforced the city as “the unchallenged nucleus for preserving the image of Bach”, a composer who has always taken a backseat to his grandiose compositions.

First painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann in 1748, the portrait is said to be the most well-preserved and accurate likeness of the baroque composer. Worth around $2.5m (£1.6m), it is considered priceless by Bach enthusiasts, and is now to go on immediate display.

Bewigged and jowly, with thickset features, myopic gaze and ruddy cheeks, the 63-year-old captured in the oil painting looks to have known the struggles of life but to still be able to enjoy himself, according to Sir John Eliot Gardiner.

The eminent British conductor, and one of the world’s foremost Bach experts and performers, was responsible for persuading Bill Scheide, a US philanthropist and fellow Bach aficionado who bought the portrait in 1951, to bequeath it to the city of Leipzig in his will.

“Scheide had the generosity to change his will and make the portrait an outright gift to the Bach archive, so that Bach has been able to return to his place of origin,” said Gardiner.

One of the most important cultural cities in Germany in Bach’s day, Leipzig became largely shut off from the outside world during the cold war. The painting’s return chimes well with Leipzig’s 1,000th anniversary celebrations which are largely focused on its post-1989 revival as one of Germany’s most culturally and economically vibrant cities.

After a short farewell ceremony following Scheide’s death last year at the age of 100, the painting was flown in April from his home in Princeton, New Jersey, to Leipzig, where Bach spent his most productive years as cantor of the St Thomas boys choir, from 1723 until his death in 1750, and where he wrote what are widely considered to be his best works.

Gardiner said an encounter with the painting brought the viewer closer to one of the greatest musical geniuses of all time who, despite his prominence, remains a very impersonal man.

“Because of the poverty of primary evidence objects surrounding Bach’s life, we know pathetically little about him,” he told the Guardian. “So when you get a fully-authenticated object like this, it is most exciting.”

The painting was inherited by Bach’s second eldest son, CPE Bach, who passed it on to his widow and daughter. Via Berlin and Hamburg, it was later bought in a junk shop in Breslau (now Wroclaw) in Upper Silesia in the 19th century by the Jenke family.

In 1936, Walter Jenke, a German-Jewish refugee, escaped Nazi Germany to Britain, bringing the painting with him and it ended up in Dorset.

In a sneak preview of the work ahead of the unveiling in the sacristy of St Thomas’, where it was guarded by four bodyguards, Gardiner gave the portrait a knowing look, as if he were acknowledging the presence of an old friend. That’s because he grew up with the painting, which was brought to his family, he says, “by serendipity”.

Jenke entrusted it to Gardiner’s father, a close friend of his, at their home in Fontmell Magna in Dorset a few years before the conductor’s birth. “And from the time I could walk, until I was 10, I must have passed it on our first floor landing four or five times a day,” he said. “We had a low-ceilinged thatched house, so his eyes were on a par with mine every time I met him on the landing. I found him very foreboding.

“Maybe it was the wig and that rather severe expression, but I didn’t get beyond that, and I couldn’t connect the incredibly ebullient and joyous music I was learning as a kid – the Brandenburg Concertos and the motets – with this rather stern looking kapellmeister [conductor]. It was only much later in life that I started to look at it in a different way.”

In 1951, Jenke was forced to sell the painting to finance his family’s upkeep, to Bill Scheide, in whose living room it hung for 60 years. “As a Bach lover, what you want above all is for him to leap out at you and be full of energy and defiance and vitality,” Scheide said. “That’s partly there, but he’s a mix of the cerebral and the sensual, the same dichotomy that’s replicated in his music.”

The 72-year-old said he had learned to view the painting in two sections.

“When you look above the nose, you see very much the pedagogue, the Kapellmeister, the intellectual ... then look from the bridge of the nose downwards, and you see the flared nostril, the curl of the lips, the double chin, and suddenly you see the father of 22 children and the bon viveur who was manifestly fond of his grub and his wine and beer.”

He also sees traces in Bach’s eyes of the diabetes he suffered from, of the numerical puzzles posed by the buttons on his jacket and the music score, and is bemused by his peculiar dark eyebrows, which are combed towards the bridge of his nose.

Judy Scheide, the widow of Bill Scheide, said that when she married her husband, she married two men. “Bill and Bach, who hung on the living room wall. Right until the end, he would greet the portrait with ‘Good morning, sir’ ... and every night with ‘Goodnight, sir’.”

She said she was honoured to fulfil her late husband’s wishes and bring the portrait back to its real home.

Gardiner, who became the president of the Bach archives in Leipzig in 2014 – in which capacity he oversaw the ceremony of the painting’s return – still believes the portrait has many secrets to reveal.

He said Leipzig’s team of “truffle-hound Bach researchers” had “only half cracked” the intrigues surrounding the manuscript that Bach holds in his right hand towards the viewer, which Gardiner refers to as an invitation to us to look closer. “The score is of a six-part canon with only three lines that he’s looking at upside down and back to front.”

When read in reverse, the other three lines emerge. But there’s also a rectangle-shaped pentimento concealing part of Bach’s dark blue jacket. “I’d love to see what’s under that – perhaps another clue to the music,” said Gardiner, suggesting the painting might be x-rayed.

The city is in possession of another Haussmann portrait, painted two years previously, but it has been so badly restored it lacks any of the vivacity of the 1748 version – which has only once been altered, after Scheide’s son accidentally pierced it with a dart during a birthday party.

Choir boy Leon Taege, 18, who has sung with the Thomanenchor since the age of nine, attempted to sum up his and his fellow choir boys’ feelings ahead of their performance of a sacred cantata written by Bach for the inauguration of Leipzig’s new town council.

“We’re pretty excited,” he said. “We’ve lived with a copy of the portrait, which has hung in one of our practice halls for as long as I can remember, and it’s always evoked mixed feelings in me of both fear and warmth. The eyes follow you around, which as a nine-year-old made a big impression on me, so seeing the real thing is something quite special.”