Marin Alsop: Bernstein the inspiration

Bernstein was impossibly brilliant in so many different areas: a genius conductor, composer, author, pianist, thinker, activist, educator and entertainer. But for me, his genius was in connecting the dots between all of these. Everything he read and experienced influenced everything he thought and did. I think he once said that he didn’t know whether he loved music or people more.

He had passion, enthusiasm and intense and boundless curiosity about our world. Bernstein did not think about education and music as being separate entities; for him, they were part of a systemic, organic, whole-person educational approach. He was at the forefront of interdisciplinary learning - both a radical new concept and a harkening back to the Greeks. Education as a whole was important to him: information as food, nutrition, a source of power and, most importantly, possibility.

When I was growing up in New York, Bernstein was an integral part of the city’s life. I remember seeing him on TV on Sunday afternoons and going to hear New York Philharmonic Young People’s concerts. After one of these, when I was about nine, I said to my parents: “I want to be a conductor.”

I would have gone to the moon to work with Bernstein. In fact, I studied with him at the Schleswig-Holstein festival in northern Germany in 1987 and then at Tanglewood [the Massachusetts festival centre], before I accompanied him to Japan. There were so many important things he taught me: that our first priority as conductors is as a messenger for the composer; that every piece has a narrative, a story, often with a moral; that it is our responsibility to discover that story and convert it convincingly.

Bernstein was the consummate amalgam of high-brow, low-brow and every other brow. He ascribed to Duke Ellington’s view: there are two kinds of music, good and bad. West Side Story is one of the most skilfully written musical pieces of all time. He remains the benchmark for outreach and engagement.

Marin Alsop conducts the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in Bernstein’s Slava! (A Political Overture) and his Second Symphony at the Proms on 27 August.

John Mauceri: Bernstein the conductor

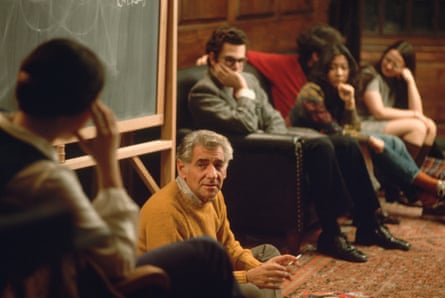

I first met Bernstein in 1971. I became his assistant, then editor, and I conducted many of his works. The first thing he told me, as we sat down for a sandwich, was that he believed that every masterpiece was built on a single tempo, and all the speeds of the music through the entire work are related to that central spine.

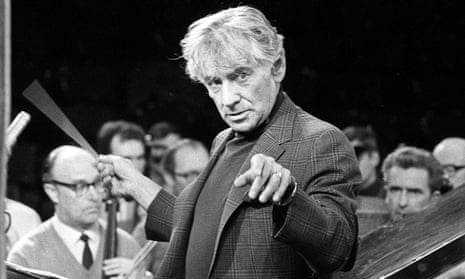

He was a very physical conductor. He would leave the ground on the upbeat - his style was not to everyone’s taste. “I’ve yet to have anyone demonstrate,” said Pierre Monteux, “that an orchestra plays louder because you jump higher.” His was certainly a unique way of expressing music, historically closer to how Beethoven or Berlioz were described as conducting. He told me he hated the way he looked when he conducted, adding “but when I do it I get the sound I want.”

For him, Beethoven was the greatest composer of all time - his very first TV show was on Beethoven’s 5th symphony. Beethoven never lets you down, he said, because everything he wrote sounds inevitable. He was uncomfortable conducting Wagner: as a Jewish man, he found it difficult to separate his music from his anti-semitic writings and way it was used by the Nazis. He loved the wit and balance of Haydn, though, and was particularly celebrated for his interpretations of Mahler, a composer very close to his heart.

If Lenny’s performances were a collaboration between his live audience and his live musicians, when he recorded he became Lenny the rabbi - the docent who wanted to illuminate the ancient texts. All conductors are storytellers and Lenny was one of the best. He’d come out onto the stage, bow, shake hands with the orchestra’s leader, and wait, wait for the audience to be paying attention. One of the things I miss most about him is his ability to tell a joke, because of his timing. Timing is everything in classical music.

John Mauceri is the author of Maestros and their Music: the Art and Alchemy of Conducting.

Barry Seldes: Bernstein the activist

From his early childhood until his death Bernstein was unwavering in his support for liberal causes. He was politically active all his life. As a student in the 1930s, he directed a production of The Cradle Will Rock, Marc Blitzstein’s opera about corruption and corporate greed. The local police reported him to the FBI, whose file on the young musician grew over the subsequent 15 years as the McCarthy era approached. Not only was Bernstein subject to FBI spying for his support for wartime Russian relief, and postwar support for refugees from fascism, but also for his support for civil rights for African Americans.

In 1949, Bernstein was labelled a communist and blacklisted, his music banned by the CBS network and from the movies. Only in 1953, when he signed an 11-page affidavit saying he was not a communist, was he allowed his passport back. He was removed from the blacklist, hired by Warner Bros to compose the music for the film On the Waterfront, and appeared on CBS. By 1957, as music director of the New York Philharmonic, he was fully rehabilitated.

Under President Kennedy, a personal friend, Bernstein was emboldened to speak publicly on behalf of the civil rights movement. He was part of the Stars for Freedom rally, a concert organised by Harry Belafonte to inspire the 25,000 marching from Selma to Montgomery to demand voting rights. He marched against the Vietnam war, but when, in 1970, he hosted a party to raise funds for Black Panther associates charged with criminal activity, and, moreover, supported the anti-war activist Daniel Berrigan, he found himself on the wrong side of not just the FBI but most of the liberal media. Luckily for Bernstein, Watergate destroyed Nixon, and Hoover died, before they could destroy the conductor’s career.

Barry Seldes is the author of Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician (University of California Press, 2009)

Humphrey Burton: Bernstein the TV star

I was often in the US in the early 1960s making films for [BBC arts programme] Monitor, so I saw at first hand how Lenny Bernstein’s outsize personality dominated the American television screen. He came over as warm-hearted, clever, inclusive, exciting. His was the greatest influence on us programme-makers when we started BBC2 and expanded six-fold the amount of classical music on television. Younger readers can have no idea of the influence he wielded, how he created an appetite for classical music among the general public.

For a decade from 1954 he delivered televised essays intended for grown-ups. Beethoven’s sketchbooks, the development of American musical comedy, what makes opera grand? Such subjects were grist to his mill: he was a born communicator and he had stimulating, jargon-free things to say about a broad range of musical subjects. When music director of the New York Philharmonic (in 1958, the first American in that post) he insisted on a clause ensuring four televised Young People’s Concerts each season. With only three TV channels on the air, those YPCs could pull in a prime-time audience of 30 million. He certainly changed my life – I hope for the better – and I count the writing of his biography, along with the creation of Young Musician of the Year, as the most useful things I have done with my four score years and seven.

Humphrey Burton’s biography of Leonard Bernstein (1994) was recently republished by Faber with a new introduction.

Jamie Bernstein: Bernstein the father

He was an incredibly attentive and affectionate father. Of course there were many prolonged absences when he was travelling, and sometimes I found it frustrating to share him with the rest of the world, but when he was at home he was always really present. We’d have big dinners and play word games and have proper family time, my parents, my younger brother and sister and I. He loved to share anything he was excited about, and that was everything from Lewis Carroll to Gilbert and Sullivan to vaudeville routines he remembered from his childhood.

It was like he was two different people trapped in one body. There was the gregarious side who was always the last one standing at the party – that was the conductor and teacher in him; but then there was the composer side – and to compose you need solitude. Composing was always a tortuous process. He hated being alone, but he had to do it.

He thought of himself primarily as a composer and I think he’d have been particularly thrilled to find how his music is being performed and celebrated around the world in this centenary year. And it sounds better than ever - as fresh as a daisy. During his lifetime a “serious” composer was supposed to write 12-tone music - but because he kept writing those pesky melodies he was never embraced by academia and recognised as the great composer that he was. He’d have liked to have been celebrated more for his music during his lifetime but it wasn’t to be - it used to sometimes make him mad, but never for long. He accepted how things were, and he spent his life trying to make the world a better place. He wanted to use his music to say what was true, to raise consciousness and be an advocate for peace. Today’s young musicians are so different from their predecessors – there is no longer the premium on their being in the ivory tower, and they’re so much more involved in the world about them. They’re called citizen artists – an expression I love, and I think my father was Citizen Artist No 1.

Jamie Bernstein is the author of Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein.

Drew McOnie: Bernstein’s musical theatre

When I was young we would play cassettes of musical theatre in the car. I had two favourite songs I would play again and again: New York, New York (from On the Town) and West Side Story’s Dance at the Gym. It was only years later that I came to realise that they were both in fact written by the same person! Like so many people, the first Bernstein work I got to know well was West Side Story. I was thrilled by its combination of emotional expression through the music and the choreographic genius of Jerome Robbins. There can have been no better example of pure collaboration, of both art forms truly inhabiting the other. Bernstein’s music theatre always tells you a story. He doesn’t ever give you a toe-tapping tune just because the audience expect one at that point. He created fully formed emotional intelligent worlds in which his characters can truly live. It’s still today rare that the danced elements of shows take on any meaningful narrative responsibility. Bernstein and Robbins created huge moving dance sequences that, along with the almost operatic vocal requirements, put total confidence in each of the respective disciplines and say: “Go on ... you can do it ... we believe in you.”

His work certainly requires a level of discipline of its performers that is off the chart. I directed and choreographed On the Town for Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre last summer. It was terrifying to approach technically, but so thrilling to dance even if he’s cruel to choreographers’ brains! Before we started rehearsals I worried it was going to be challenging to get an entire company to hear and feel the music in the same way, but the music is so startlingly instinctual it was not a problem. Bernstein has that thing – in bucketloads – that makes a dancer’s spine tingle. The key to directing his work is simply to listen the inspiration that the music gives you. He believed that music theatre can be art of the very highest form. If we all led with our hearts rather than our minds and our concerns about what others might think, we might all get a little closer to his brilliance.

Drew McOnie is currently directing and choreographing Baz Luhrmann’s Strictly Ballroom in the West End, and King Kong on Broadway.

Antonio Pappano: Bernstein the symphonist

I wanted to celebrate Bernstein’s centenary differently and decided on the symphonies as a cycle, works I hugely admire. I’ve recorded all three with the Orchestra of the Academy of Santa Cecilia, and bring one to the Proms. Bernstein loved the colour and warmth of the orchestra. His compositions were maligned by many of his contemporaries – he didn’t fit into the music of Darmstadt, of Boulez, of the avant garde – but Lenny did more for American new music than all the rest put together.

Bernstein describes his symphonies as a crisis of faith, but always looking for redemption, for renewing that faith. Look what God throws down at us - it’s tough to be Jewish, tough to be Christian, tough to be religious - is the overriding theme of the cycle. His first symphony, Jeremiah, was written in 1942 - a time when the world was in a very dark place. His third and final symphony, Kaddish (1963, rev 1977) is a response to the assassination of JF Kennedy, the text of its narration written by Bernstein himself and conceived for his wife.

I watched him conduct Copland’s Third Symphony with the youth orchestra in Tanglewood. His relationship with the older composer was close, and it was a very important piece for him, the work was somehow so inside him that he copied shamelessly from it. Many gestures, in Bernstein’s first symphony and also at the end of his second, The Age of Anxiety, come from that Copland symphony. The falling fourths, certainly, but you can hear them in Mahler’s Symphony No 1 too, another composer who influenced Bernstein profoundly. Bernstein’s reputation as a conductor has, for some, overwhelmed his identity as a composer. He probably remained bitter about that, but he’s one of those composers where you can take every bar of his music and reference it back to something else and yet, like other great composers, you play three notes and you know it’s Bernstein.

Antonio Pappano conducts the Orchestra of the Academy of Santa Cecilia in Bernstein’s first symphony at the Proms on 10 August. Pappano’s Bernstein: The 3 Symphonies is out on 10 August on Warner Classics.

Scarlett Strallen: Bernstein the singers’ favourite

I don’t think I fully appreciated the true genius of Bernstein until I came to learn the Candide score. Cunegonde is easily the favourite character I’ve ever played. She starts out as a tragic victim and then there’s this delicious flip, and things get simply hysterical. Her most famous aria, Glitter and Be Gay, her embrace of all things sparkly and glittery, is the very height of her madness, reflected in the music – which goes up a high E-flat. It’s incredibly difficult to sing, you need to be completely accurate, but also make it sound effortless.

But it’s all there in the music - all a singer needs is to get out of the way and deliver what Bernstein wrote in the score and the character comes to life. It’s all done for you in the writing. For me, Bernstein’s genius is like Shakespeare or Sondheim’s – every single note or word is intentional for the character. He understood singers completely, and asks all his musicians to push themselves to ridiculous limits, but it always feels so natural. It’s almost like it happens without you even knowing it. I think of it as using your voice to dance with the music. I love to watch footage of Bernstein conducting. He’s dancing about and having such fun.

Scarlett Strallen performs with John Wilson and the Oslo Philharmonic in the Best of Bernstein gala concert on 22 and 23 November 2018 at Oslo Konserthus.

Alex Ross: Bernstein and America today

Bernstein’s musical reputation seems more elevated today than it was in the years immediately following his death. As the works emerge from the huge shadow of his personality, they show their quirky virtues: the command of multiple musical languages, the daring juxtapositions of genre and style, the political outspokenness, and, of course, the sheer fluency of invention. Mass, in particular, is in the ascendant: whatever one might think of it, the conceit is extraordinarily original, even avant-garde. A Quiet Place is also slowly making its way. I wasn’t entirely convinced when I saw the New York City Opera stage the work in 2010, but the new Decca recording of a reduced chamber version, with Kent Nagano conducting, makes a strong case for the piece as a raw, honest, almost seismographic record of the fractures at the heart of the American dream.

Bernstein’s candour, his inability to say anything other than what he really meant, is what we miss most today. One can only imagine what yawps of rage the spectacle of Donald Trump would have elicited from him. The outward-looking, all-embracing America that Bernstein knew, loved and embodied seems very far away.

Alex Ross is the New Yorker’s music critic and the author of The Rest is Noise and Listen to This.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion