By William Clarkson

HRNM Educator |

| USS Essex under sail (NHHC) |

The War of 1812 saw the rise of the United States Navy through the actions of many famous ships and captains. The actions of USS Essex, its crew, and Captain David Porter stand out as exemplars of the importance of the war in developing the U.S. Navy and placing it on the world stage. Largely funded by the people of Salem, Massachusetts, Essex was launched September 30, 1799. The ship was approximately 140 feet long with a 36-foot beam, displacing 860 tons. Essex was originally armed with twenty-six 12 pound long guns and ten 24 pound carronades. Many regarded shipbuilder William Hackett’s design of Essex as one of the finest sailing ships in the U.S. Navy. USS Essex participated in the Quasi-War with France, as well as the First Barbary War. Notably, in 1800, Essex became the first U.S. warship to sail around Cape Horn, crossing into the Pacific Ocean to escort merchant vessels back into the Atlantic under the command of Edward Preble. However, it is Essex’s performance during the War of 1812 that makes the ship and crew one of the most successful of the early U.S. Navy.

|

| Captain David Porter, circa War of 1812 (NHHC) |

In the summer of 1811, USS Essex received its latest commanding officer in Captain David Porter at Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, VA.[i] Captain Porter immediately wrote to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton, complaining that a previous captain had swapped most of the long guns for carronades. He wrote, “Was this ship to be disabled in her rigging in the early part of an engagement, a ship armed with long guns could take a position beyond the reach of our carronades and cut us to pieces.” By some accounts, the change in the ship’s armament also reduced the ship’s sailing qualities, negating the advantages of William Hackett’s balanced design. Despite Porter’s disdain for carronades, he spent the following months drilling Essex’s crew so if they were called upon, they would be ready and capable. When the U.S. declared war with Great Britain on June 18, 1812, the Navy sent Essex to the Caribbean waters off Florida to hunt for an English convoy allegedly carrying specie and supplies. Failing to locate this convoy, Essex spotted a different flotilla and succeeded in isolating and taking a ship named Samuel and Sarah, which was loaded with British troops. Without the means of taking the soldiers, Porter confiscated $14,000 worth of goods and specie. This capture marked the beginning of Essex’s seizure of prizes in the Caribbean over the span of its eight-week cruise. |

| USS Essex briefly engages with and captures HMS Alert on August 13, 1812 (NHHC) |

Merchants and cargo vessels were not the only prey for David Porter and USS Essex, however. On the morning of August 13, 1812, Essex spotted the 20-gun sloop of war, HMS Alert. The crew’s training paid off in this encounter. In a planned maneuver, Porter ordered the gun ports to remain closed and his crew took steps to make Essex appear to be a slow-sailing merchantman. Captain Thomas Laugharne took the bait. Only too late did he realize that the ship he was approaching was a military vessel. After just eight minutes of combat, unable to match the overwhelming firepower of Essex’s carronades at close range, Laugharne ordered Alert’s colors struck and surrendered to Porter. This marked the first British warship taken by a U.S. warship in the War of 1812. Porter ordered Laugharne to take his ship to Newfoundland and disembark his crew before taking it to New York and surrendering the ship to U.S. authorities there. Bound by tradition and honor, this is exactly what occurred. On September 7, 1812, Essex evaded the British blockade and entered Delaware Bay to reprovision and prepare for its next foray, with David Porter writing, “I have the satisfaction to reflect that I have been a great annoyance to the enemy. The injury I have done them in less than two months may be fairly estimated at $300,000. I hope, however, to have another slap at them ere long that will gall them still more.” |

| Essex and prizes in a U.S.-controlled bay in the Marquesas Islands c. 1813 (NHHC) |

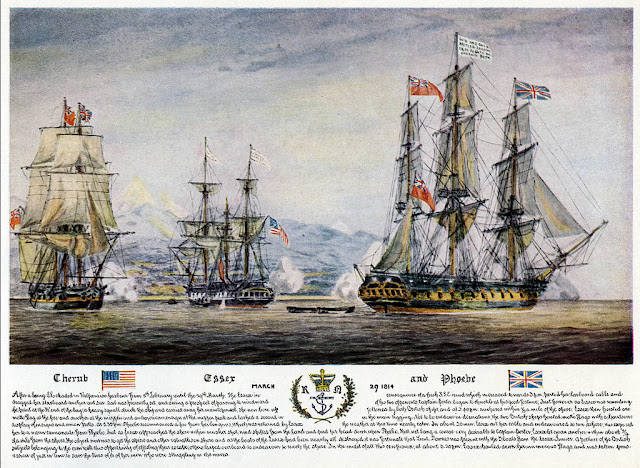

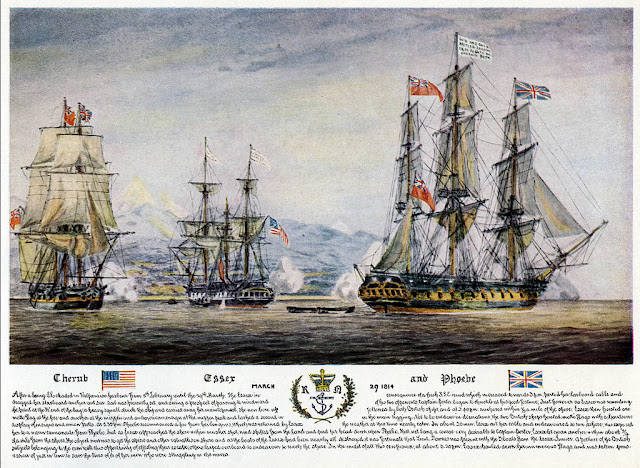

Following this successful first cruise, Essex set sail once more. After spending some more time in Atlantic waters, Essex made its way to the Pacific, where the ship took prizes from the British whaling fleets. Essex’s success continued until February 1814. On February 3, 1814, Essex, along with a captured and converted whaler (Essex Junior) arrived at Valparaiso, Chile.[ii] Five days later, two British vessels, HMS Phoebe (36-gun frigate) and HMS Cherub (28-gun sloop), appeared at the port. They were both under the command of veteran Captain James Hillyar. Essex was effectively trapped. While none of the belligerents dared to break the neutrality of the port, several weeks of challenges, insults, and saber rattling followed. Finally, on March 28, 1814, Captain Porter decided to make a run for open water and ordered the ship to get underway. Phoebe and Cherub quickly gave chase. Then, as if by fate, Essex’s main topmast broke and fell into the ocean, ensuring that Essex would not be able to escape the British pursuit. Porter ordered Essex into a small nearby bay and prepared his crew for the inevitable engagement. After some initial close-range combat between Cherub and Essex, Captain David Porter’s prediction from three years earlier now occurred. With Essex’s mobility limited as the battle unfolded, Phoebe and Cherub stayed just out of range of Essex’s carronades and blasted the ship with their long guns. Between 4 and 6pm the battle raged, until finally Porter gave the order to strike Essex’s colors. Of Essex’s 255-man crew, 58 were dead and 65 wounded. Aboard the British vessels, only five crewmen were killed and 15 wounded. Porter and Essex’s crewmembers were paroled[iii] and released to sail back to the United States aboard Essex Junior. |

| Battle between USS Essex, HMS Phoebe, and HMS Cherub on March 28, 1814 (NHHC) |

Despite having lost USS Essex, when David Porter and his surviving crew arrived back in the U.S., they were welcomed and celebrated. The American Advocate, a New York newspaper, reported, “It was really pleasant to see the joy which animated the American citizens of New York where he [Porter] was received with six hearty cheers. This is the way Americans receive their heroes, tho’ they may have been unfortunate.” Porter went on to dine with President James Madison, and Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton wrote that USS Essex had “elevated the naval character of our country even beyond the towering eminence it had before attained.” Over the course of nearly two years, Porter and USS Essex had sailed both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, captured 22 ships, and managed to evade superior British forces for a substantial period. Although eventually cornered and defeated, the story of USS Essex during the War of 1812 is one of determination, resilience, courage, and ultimately sacrifice. Notes:[i] David Porter was the son of Revolutionary War naval officer David Porter Sr., and father to Civil War Admiral David Dixon Porter.

[ii] Valparaiso was a neutral port during the war, and both U.S. and British ships often stopped there to refit, resupply and rest. Porter used the port for this purpose several times while Essex was sailing in Pacific waters.

[iii] “Paroling” captured soldiers or sailors was a common practice of the period, whereby prisoners were released to return home on the condition that they will not take up arms once again to participate in the conflict. These paroles, however, were not always honored.

No comments:

Post a Comment